Bioluminescence First Evolved in Invertebrates About 540 Million Years Ago

Posted on Categories Discover Magazine

Living organisms activated a natural light source nearly 300 million years earlier than previously thought, according to a study in the Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

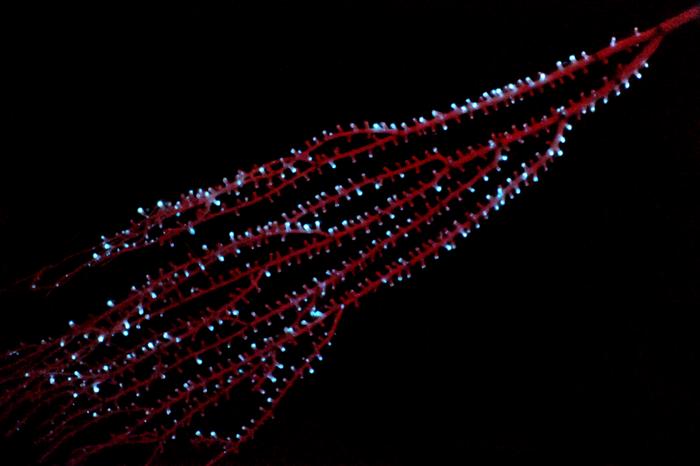

A group of scientists from the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History used genetic data and statistical modelling to demonstrate that bioluminescence — the ability of living things to produce light through chemical reactions — first evolved in marine invertebrates called octocorals about 540 million years ago.

Looking for Bioluminescence

Octocorals — or soft corals — are small polyp-shaped creatures that create a network of soft structures for their living quarters. In contrast, corals are larger and build harder structures for housing.

Until this study, bioluminescence was first thought to arise in small marine crustaceans called ostracods about 267 million years ago. The trait has been shown to independently evolve in nature 94 times.

So why choose octocorals?

The research group focused on the octocoral for three reasons. First, octocorals are among the oldest living creatures known to “light up.” Second, they have ample genetic data associated with them. And, finally, research group members had plenty of experience studying the organism, including completing an evolutionary family tree using data from 185 species.

The Octocoral Family Tree

The team built on that tree by using statistics to determine the probabilities of each branch begetting a bioluminescent species. They started with two octocoral fossils whose age they knew, placed them on the octocoral family tree, mapped out the branches that contained a gene associated with bioluminescence, then used a statistical technique to trace the probability of ancient branches also containing that trait.

They expected the trait to extend far back into the family tree, but it was a “pleasant surprise” just how far back it stretched, says Danielle DeLeo, a museum research associate involved with the study.

“We assumed the trait was going to be fairly ancient because it is an ancient group of animals and it’s highly prevalent in the group,” says DeLeo. They then ran multiple tests to try to disprove their finding — but it still held true.

Why Does Bioluminescence Happen?

Although the “when and how” of bioluminescence is now better understood, researchers still haven’t conclusively nailed down the “why.” Scientists associate bioluminescence with behaviors including camouflage, courtship, and communication, but those are just theories. “The current function in corals is a bit mysterious,” says DeLeo.

“Lighting up might well lure prey to the soft coral, or serve as a burglar alarm,” says DeLeo. “When you bump into the branches of these corals, they let off this bioluminescent light to possibly warn away potential predators.”

However, that function seems a bit sophisticated to have evolved so early. Some scientists theorize that bioluminescence was a byproduct of a chemical process that protects cells from stress. Then, as creatures grew more complicated, they saved the function because it proved useful in other ways.

The team’s work sets an earlier starting point to investigate that divergence.

Article Sources

Our writers at Discovermagazine.com use peer-reviewed studies and high-quality sources for our articles, and our editors review for scientific accuracy and editorial standards. Review the sources used below for this article:

Before joining Discover Magazine, Paul Smaglik spent over 20 years as a science journalist, specializing in U.S. life science policy and global scientific career issues. He began his career in newspapers, but switched to scientific magazines. His work has appeared in publications including Science News, Science, Nature, and Scientific American.