The Infrared Images for Dyson Spheres Could be Evidence of Star-Harnessing Alien Technology

Posted on Categories Discover Magazine

In the modern age, the search for extraterrestrial life requires a unique mind. A researcher must have the openness and creativity to imagine something beyond our current knowledge of the universe. At the same time, the researcher, if they are to be taken seriously, must also be skilled enough to analyze high-powered astronomical imagery through supercomputing, artificial intelligence, or other means.

The researchers behind project Hephaistos, a Swedish-based effort to identify traces of alien life in the cosmos, fit this bill. They are extensively published astrophysicists with a shared dream: that the observable universe may contain signs of far-away civilizations yet unrecognized.

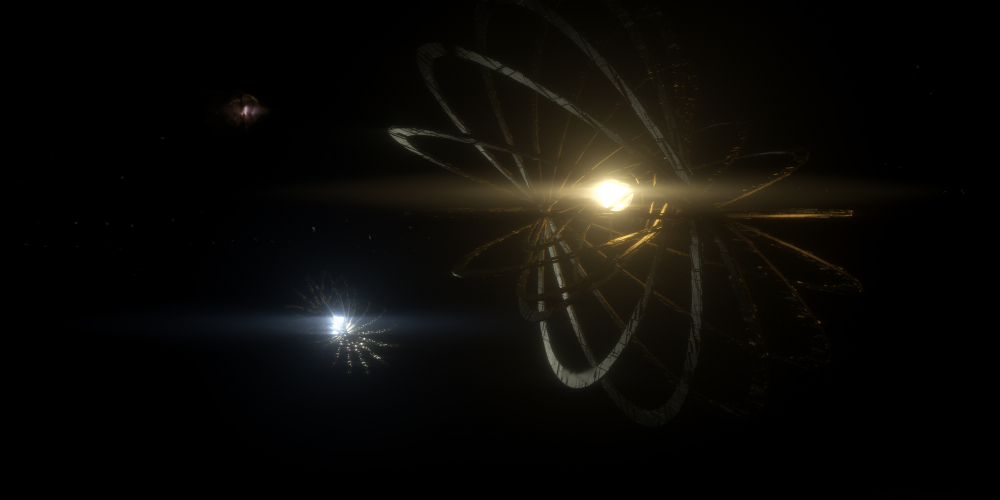

Earlier this year, the group published a paper documenting their use of machine learning to comb through large datasets of infrared images for Dyson spheres — networks of alien satellites harvesting energy from a star. The idea was old, but the scientists’ AI-forward approach was new.

“If you want to do this, you kind of have to try something that hasn’t been tried before,” says project Hephaistos leader Erik Zackrisson.

In their paper, project Hephaistos identified seven candidates for further research — star’s that appeared to be encircled by something like a Dyson sphere.

Just a couple of months after the publication, another research team called Project Hephaistos’ results into question. The truth is still being sorted out.

What Is a Dyson Sphere?

Many good hypotheses have come from science fiction, and this is especially true in the search for alien civilizations. Freeman Dyson credited the initial idea for Dyson spheres to Olaf Stapledon.

As it turns out, Stapledon’s sprawling 1937 science-fiction novel, Star Maker, includes just a brief mention of an alien civilization that could harvest the energy of stars. From this line, Dyson imagined that an advanced technological society would inevitably turn to its sun for a plentiful and consistent power supply.

According to Zackrisson, a common misconception about Dyson Spheres comes from their name. Likely, a Dyson Sphere would not actually be a sphere. Instead, it would be a web-like network of satellites in orbit around a star. The satellites would harvest energy from the star, much like solar panels harvest light energy from our sun.

Read More: What Does Extraterrestrial Mean and Why Are Experts Looking for It?

Challenges in Identifying Potential Dyson Spheres

When project Hephaistos went looking for Dyson Spheres, they programmed their model to spot stars that were partially obscured by objects that looked like they could be energy-harvesting satellites. Then, they eliminated every result that they could explain away through corrupted data or known “astrophysical phenomena.”

“The problem is that there are mundane astronomical objects that also give you infrared excess,” Zackrisson explains. “You want to get rid of those.”

Images from the project’s seven candidates look much like a shag rug with chocolate crumbs dusting its surface. What looks like shag is the intense heat produced by a given star’s nuclear fusion. And researchers are interested in those chocolate crumbs.

Like any solid object, they obscure the intense heat of the star from view. Yet, each crumb of interest also gives off a discernible amount of infrared radiation consistent with the “waste heat” that researchers would expect an energy-harvesting satellite to emit.

Read More: The Secret Origins of the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence

Could Space Dust Explain the Mysterious Infrared Images?

The British team that called Project Hephaistos’ results into question, led by astrophysicist Tongtian Ren, proposed an alternate theory. According to the researchers, Project Hephaistos’ chocolate crumbs were interference from hot, dust-obscured galaxies in the foreground. Basically, irradiated space dust – not alien civilization – was responsible for the phenomena.

Zackrisson concedes that three of the candidates seem to be hot, dust-obscured galaxies. But the mystery is not solved yet.

“The question is, what are those for which we don’t know yet. The jury is still out,” he says.

When Ren and his co-authors published their critique, the prospect of nearby alien civilizations once again seemed to lose some permanence in the collective imagination of alien enthusiasts. Yet, Project Hephaistos’ other four candidates are still awaiting confirmation or refutation. And, either way the evidence goes, one bunk result will do little to dissuade searchers — especially as new methods emerge.

“Radio SETI dates back to the 1960s,” Zackrisson says, referring to the acronym for the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence (SETI). “Back then, they didn’t have infrared telescopes. Astronomy has entered the era of big data, so we have these databases of billions of objects in the sky.”

Read More: New SETI Tool Expands the Search for Intelligent Life in the Universe

Article Sources

Our writers at Discovermagazine.com use peer-reviewed studies and high-quality sources for our articles, and our editors review for scientific accuracy and editorial standards. Review the sources used below for this article:

Gabe Allen is a Colorado-based freelance journalist focused on science and the environment. He is a 2023 reporting fellow with the Pulitzer Center and a current master’s student at the University of Colorado Center for Environmental Journalism. His byline has appeared in Discover Magazine, Astronomy Magazine, Planet Forward, The Colorado Sun, Wyofile, and the Jackson Hole News&Guide.