New Technology Could Replace Space Suit Diapers for Astronauts

Posted on Categories Discover Magazine

One of the most frequent questions astronauts get asked is, how do you go to the bathroom in space? For decades, their reply has been the same icky answer: they essentially soil their suits.

Astronauts in transit (space stations have more sanitary solutions — but even those can sometimes go awry) have long depended on what are essentially adult diapers to absorb their urine. For short missions, this is merely uncomfortable, and just a bit gross. But for longer journeys — like, perhaps ones planned to Mars — this approach can cause health problems, including serious rashes and urinary tract infections (UTIs).

A team of Cornell University engineers have developed a healthier, more comfortable approach: a system that collects and filters the urine, according to a report in Frontiers in Space Technologies.

Space Diaper Alternative

The new technology not only protects the user from urine, it transforms the liquid waste into drinkable water. That sustainable approach lessens the need for astronauts to carry drinking water and also reduces the need to store, transport, and return urine back to Earth.

The system collects the urine in a cup that covers the wearer’s genitals, vacuums it through an external catheter and directs it into an osmosis system that transforms the urine into filtered water.

An undergarment constructed from multiple layers of flexible fabric holds the fitted silicon cup in place. The cup is lined with a nylon-spandex blend, which draws urine away from the body and towards the inner cup’s inner face. A moisture sensor then activates a pump to move the urine from the cup into the filtration system.

Astronauts have long complained about what NASA calls its Maximum Absorbency Garment (MAG) – a multi-layered adult diaper made of superabsorbent polymer. The MAG has been in use since the late 1970s.

“The MAG has reportedly leaked and caused health issues such as urinary tract infections and gastrointestinal distress,” Sofia Etlin, a research staff member at Weill Cornell Medicine and Cornell University, and the study’s first author, said in a statement.

“Additionally, astronauts currently have only one liter of water available in their in-suit drink bags. This is insufficient for the planned, longer-lasting lunar spacewalks, which can last ten hours, and even up to 24 hours in an emergency,” said Etlin.

Read More: How Astronauts Go to the Bathroom in Outer Space

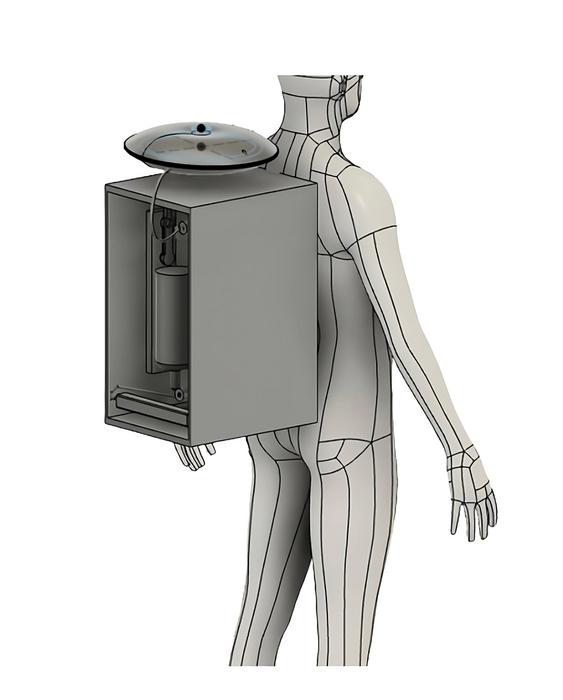

High-Tech Backpack

Longer voyages — like the planned Artemis II mission to the Moon — would be safer and more comfortable for astronauts if they had better waste management systems. A crewed mission to Mars, which is expected in the early 2030s, almost necessitates one.

While the cup and tube provide the collection for the system, a high-tech backpack contains the filtration system. Reverse osmosis removes the water from the urine, then a pump separates the salt from the remaining water. The purified water is then enriched with electrolytes and pumped into an in-suit drink bag, ready for consumption. Collecting and purifying 500ml of urine takes only five minutes.

The design will first be piloted in simulated conditions, then tried during actual spacewalks.

“Our system can be tested in simulated microgravity conditions, as microgravity is the primary space factor we must account for,” Christopher Mason, an Emory engineer and the study’s lead author, said in a statement. “These tests will ensure the system’s functionality and safety before it is deployed in actual space missions.”

Read More: Why These 6 Items Are Not Allowed in Space

Article Sources

Our writers at Discovermagazine.com use peer-reviewed studies and high-quality sources for our articles, and our editors review for scientific accuracy and editorial standards. Review the sources used below for this article:

Before joining Discover Magazine, Paul spent over 20 years as a science journalist, specializing in U.S. life science policy and global scientific career issues. He began his career in newspapers, but switched to scientific magazines. His work has appeared in publications including Science News, Science, Nature, and Scientific American.