Loss of Sea Ice in Antarctica Is “Nothing Short of Shocking”

Posted on Categories Discover Magazine

After months of summer, the sea ice fringing Antarctica has shriveled to its annual minimum. And for the third year running, scientists are shocked by just how much ice has gone missing.

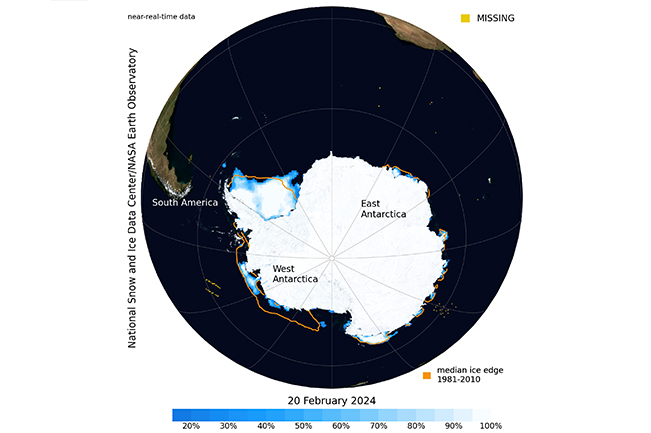

The annual minimum likely occurred on Feb. 20, tying with 2022 for second lowest in the 46-year satellite record, according to the National Snow and Ice Data Center. The all-time record low occurred last year.

This year’s minimum is 328,000 square miles below the 1981 to 2010 average summer minimum extent in Antarctica, according to the NSIDC. That’s an area of “missing” ice larger than Texas.

Sea ice is growing again as temperatures plunge with the onset of Antarctic winter. Scientists will be watching carefully to see what happens when it reaches its maximum winter extent next September.

At the height of Antarctic winter last year, sea ice was clearly in trouble. After months of growth, it maxed out at 676,000 square miles below the long-term average. This set a new record low for the winter maximum extent by a wide margin. And this time, the extent of missing ice was almost as large as Mexico.

The red line shows the current sea ice extent in Antarctica compared to the 1981-2010 median, in blue. (Credit: Zachary Labe)

“Antarctica’s low sea ice extent in 2023 and culminating with this low 2024 minimum is nothing short of shocking,” says senior research scientist Ted Scambos of the Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences, quoted in an NSIDC release. “These consecutive lows have the potential to kick off real changes in ice sheet melting, snowfall on the ice sheet and warming of the surrounding ocean.”

But Scambos cautions that the extent of sea ice in Antarctica has tended to fluctuate significantly in the recent past. Just 10 years ago, it was setting record highs.

Scientists aren’t sure what’s behind these dramatic fluctuations in Antarctic sea ice. But shifts in sea and air temperatures, winds, and ocean currents are likely implicated, with both natural variability and human-caused climate change in play. Because of this complexity, scientists can’t rule out a rebound.

That said, recent research has found evidence that the Antarctic sea ice system has reached “an abrupt critical transition.” This means we may have entered a period of sustained declines. That would be bad news.

Here’s Why You Should Care About Antarctic Sea Ice

Sea ice shields thick shelves of floating ice that extend from Antarctic glaciers, helping to slow their flow into the sea. With less of a sea ice shield in front of the ice shelves, waves are freer to pound on them, weakening and fracturing them. This can allow the glaciers behind them to flow more rapidly into the ocean, thereby accelerating sea level rise.

Sea ice also reflects sunlight, helping to keep conditions cold. By contrast, ice-free water is dark and therefore tends to absorb solar energy. These now warmer waters can eat away at the giant, buttressing ice shelves from below.

As part of NASA’s Operation Ice Bridge, an overflight of West Antarctica on Nov. 5, 2016 revealed ice in the process of calving from the front of the Getz Ice Shelf. Research suggests that warming waters are eating away at West Antarctic ice shelves from below. As the shelves weaken, they allow glaciers behind them to flow more quickly. The result: More ice from the Antarctic landmass is flowing into the sea, raising sea level. (Credit: NASA Earth Observatory)

Floating ice shelves can buttress the glaciers behind them because they tend to become pinned by high spots on the sea floor. But research published this month revealed that thinning of ice shelves above these pinning points accelerated significantly between 1989 and 2022.

“A continuation of this trend would further reduce the buttressing potential of ice shelves, enhancing ice discharge and accelerating the contribution of Antarctica to sea-level rise,” the authors wrote in the study, published Feb. 21 in the journal Nature.

This phenomenon is particularly concerning for the West Antarctic Ice Sheet. The WAIS is drained by the Thwaites Glacier — hyperbolically labelled the “Doomsday Glacier” in some media accounts — along with its sibling, the Pine Island Glacier. Over the past three decades, the amount of ice flowing from these glaciers into the sea has doubled, raising concerns that an unstoppable, runaway “collapse” of the WAIS has begun.

Currently, the Thwaites Glacier alone — at 80 miles across, the world’s widest glacier — is raising sea level globally by about 1.5 inches per decade. That’s roughly 4 percent of the total.

Should the Thwaites Glacier disintegrate, global sea level would rise by about two feet. This also would destabilize the West Antarctic Ice Sheet, which holds enough ice to raise sea levels by more than 10 feet. Although a full collapse of the WAIS into the sea would likely play out over centuries, we’d nonetheless experience serious impacts sooner than that.

In the interest of full disclosure, Ted Scambos is a colleague of mine at the University of Colorado, home to both the Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences, where he works, and the Center for Environmental Journalism, which I direct. But we do not work together.