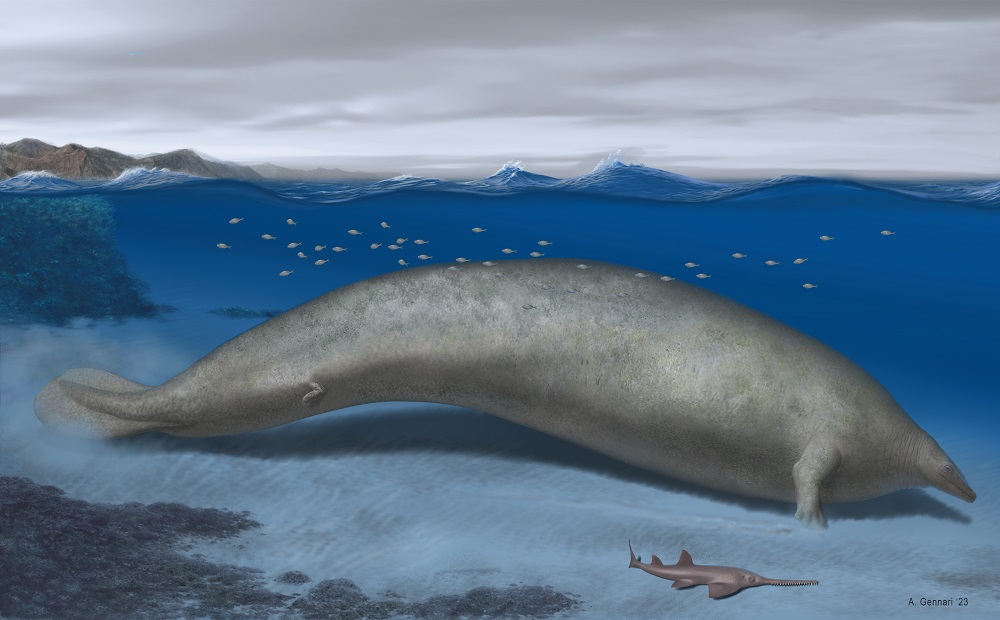

Is an Ancient Whale That Resembles a Massive Manatee the Heaviest Animal Ever?

Posted on Categories Discover Magazine

A massive new whale discovered in the Peruvian desert presents a caloric quandary: At somewhere between 170,000 and 680,000 pounds, it would have required an equally massive diet to survive. Yet, Perucetus colossus was a slow, ponderous sort of sea creature that kept to the shallows and coastal regions.

So, what did it do?

Like many modern whales, it may have relied on filter feeding, or it may have munched on sea grass like a manatee. Or it could have suctioned up demersal fishes, crustaceans, mollusks or other slow-moving prey.

Then again, it might have used its triangular teeth to tear off pieces of dead sea creatures, a strategy normally practiced by sharks. Bit by bit, the great whale – which is in the running for the heaviest animal of all time – would have survived.

Really Big Bones

The current record-holder, the blue whale, weighs somewhere between 290,000 and 330,000 pounds, which includes a heart the size of a small car. While researchers don’t know the size of P. colossus’ heart, they do know it boasts a 65-foot skeleton that weighs two-to-three times that of a blue whale. Evolution selected for this creature to have an extravagant set of bones, and it selected hard.

Read More: Blue Whales Chase the Wind to Hunt Tiny Prey

Their fossils presented quite a challenge for paleontologist Mario Urbina after he found them in the Peruvian desert in 2010. He showed photographs to his colleagues, but the hulking shapes half-buried in sediment looked too large to be bones and created only confusion.

Urbina had found 13 vertebrae that weighed more than 220 pounds each and ribs bones that spanned nearly 5 feet. Over several campaigns, he and his colleagues transported the fossils to the Museo de Historia Natural in Lima and classified them as a new species of basilosaurid whale, an early relative to modern whales and dolphins. Urbina also dated the new specimen at 39 million years old, somewhat early for a basilosaurid.

Heavy, reinforced bones are common in shallow-dwelling sea creatures, such as manatees, which need the extra mass for ballast. Modern whales that live out in the deep ocean tend to have much lighter bones.

P. colossus vertebrae on display at the the Museo de Historia Natural in Lima. (Credit: Rodolfo Salas-Gismondi/Niels Valencia)

How Did the Whale Evolve?

To explore the shallows, P. colossus may have swam in a manner similar to manatees or undulated the rear part of its body to produce thrust. Two vestigial hind legs may have helped it paddle along, or they may have moved little at all.

Not much is known for sure about how the innovative basilosaurids (“king lizards”) evolved. At some point, four-legged tetrapods that had lived in the water some 300 million years ago decided to submerge themselves once again, perhaps to avoid predators. This most likely happened in stages, like a reverse version of The Ascent of Man.

Scientists have proposed that hoofed animals called artiodactyls took part in this transition, and a 2007 paper points to a raccoon-sized animal in particular. This indohyus, or “India’s pig,” was an important early predecessor to basilosaurids, which were the first whales to live a completely ocean-based lifestyle.

The paper found a compelling piece of evidence in the pig’s ear – a fossilized structure that whales alone have and use for underwater hearing.

Read More: Genetic Deep Dive Helps Explain How Whales Evolved to Become Aquatic