Evidence of Ancient Beaches Shows Us a Mars With Large, Ice-Free Oceans

Posted on Categories Discover Magazine

Ancient Mars may have been a beach paradise 4 billion years ago. A new study published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences reports that the Chinese Mars rover Zhurong detected evidence of an underground beach in an area that may have once been an ocean.

Though Zhurong is now inactive, the evidence the rover has collected is vital to understanding the Red Planet’s history. These findings also help support the theory that Mars once had a massive ocean.

“The structures don’t look like sand dunes. They don’t look like an impact crater. They don’t look like lava flows. That’s when we started thinking about oceans,” Michael Manga, a University of California, Berkeley professor of Earth and planetary science and co-author of the study, said in a press release.

What Lies Beneath Mars’ Surface

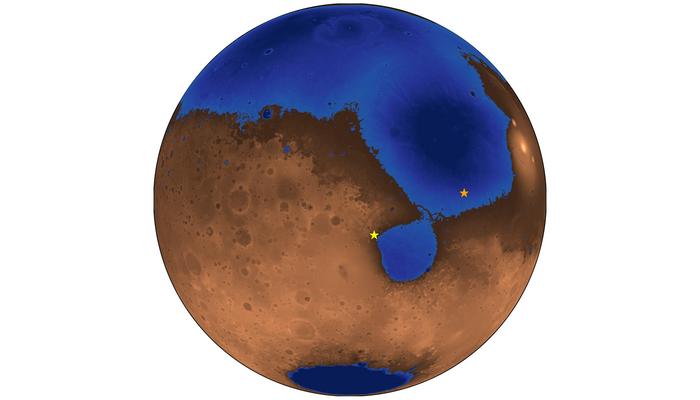

On Earth, ocean tides and winds carry sediment toward the shoreline, where the sediment settles out to form a beach deposit with a characteristic dipping angle. New observations indicate that early in its history, Mars also had an open ocean with tides and wind-driven waves that deposited sediment on the beach. (Credit: Hai Liu, Guangzhou University, China)

Zhurong landed on Mars in May 2021 and operated for a year. During that time, the rover traveled about 1.2 miles along escarpments researchers believe were once part of an ocean shore 4 billion years ago.

As the rover moved, it used a process known as ground penetrating radar (GPR) to map up to about 260 feet below the surface. Experts use GPR on Earth to look for underground utility lines, pipes, and even unmarked graves.

Along the entire route, the GPR images showed layers of a thick material, which had the consistency of sand, that pointed toward the presumed shoreline at a 15-degree angle. This is nearly identical to beach deposit angles on Earth. According to the study, it takes millions of years for deposits like this to form on Earth, so the evidence suggests that Mars once had a large body of water with waves that moved sediment around.

Read More: Wave Ripples Prove the Existence of Ice-Free Lakes on Ancient Mars

Evidence of Past Life

Schematic showing how a series of beach deposits would have formed at the Zhurong landing site in the distant past on Mars (left) and how long-term physical and chemical weathering on the planet altered the properties of the rocks and minerals and buried the deposits. (Credit: Hai Liu, Guangzhou University, China)

According to the study authors, beaches indicate that Mars once had a large, ice-free ocean, back when the planet likely had a warmer and thicker atmosphere. There may have even been flowing rivers that brought sediment into the ocean.

“The presence of these deposits requires that a good swath of the planet, at least, was hydrologically active for a prolonged period in order to provide this growing shoreline with water, sediment and potentially nutrients,” said co-author Benjamin Cardenas, an assistant professor of geosciences at Penn State, in a press release.

Though Mars is now much too cold for liquid water, it may have once sustained much more life.

“This strengthens the case for past habitability in this region on Mars,” said Hai Liu, a professor with the School of Civil Engineering and Transportation at Guangzhou University, in a press release.

Shifting Tides

After the Viking spacecraft photographed Mars in the 1970s, researchers noted that what they believed to be a shoreline in the northern hemisphere had irregular shorelines. Instead of being level, like the ones on Earth, the shoreline had dips of up to 6 miles. This made scientists doubt the ocean theory.

However, in 2007, after further study, Manga and other colleagues proposed a theory that the planet’s massive volcanic region, Tharsis, which contains the largest volcanoes in the solar system, may have altered the planet’s rotation as it formed 3.7 billion years ago and altered the shoreline. In 2017, he revisited the study and suggested that Tharsis altered Mars’ rotation 4 billion years ago.

“Because the spin axis of Mars has changed, the shape of Mars has changed. And so what used to be flat is no longer flat,” Manga said in a press release.

The Zhurong findings add to the growing evidence of water existing on Mars.

“To make ripples by waves, you need to have an ice-free lake. Now we’re saying we have an ice-free ocean. And rather than ripples, we’re seeing beaches,” Manga said.

Read More: Mars Contains an Ocean’s Worth of Water – But It’s Deep Below the Surface

Article Sources

Our writers at Discovermagazine.com use peer-reviewed studies and high-quality sources for our articles, and our editors review for scientific accuracy and editorial standards. Review the sources used below for this article:

A graduate of UW-Whitewater, Monica Cull wrote for several organizations, including one that focused on bees and the natural world, before coming to Discover Magazine. Her current work also appears on her travel blog and Common State Magazine. Her love of science came from watching PBS shows as a kid with her mom and spending too much time binging Doctor Who.