El Niño’s End is Nigh, its Fate Sealed by a Chilly Phantom Rising From the Ocean Depths

Posted on Categories Discover Magazine

As you may have heard, the El Niño that has been contributing to severe weather in California and elsewhere is expected to fade between April and June. Moreover, its sibling, La Niña — which also can have a big impact on our weather — stands a good chance of taking center stage in the fall.

But does this means a significant change in weather patterns will be happening soon? That’s what the Weather Channel recently told its viewers: “El Niño giving way to La Niña means a warmer than average spring for most of the country. And the new outlook…shows most of the northern tier Rockies and Plains will see warmer than average temperatures.”

A Weather Channel outlook for spring says El Niño is transitioning to La Niña, and this will bring warmer than average temperatures across most of the United States, including much of the southern tier of states stretching from California through Texas and beyond. But there’s one problem: It’s El Niño that typically brings warmer than average conditions across that region. (Credit: Screenshot of Weather Channel video)

There’s actually a big issue with this: We are, in fact, still in the latter stages of what has been a strong El Niño. And while it’s looking increasingly likely that it’s climatic sibling, La Niña, will ultimately push it aside, this is not imminent. The upshot is that El Niño will likely continue to influence weather patterns for the next few months.

Moreover, NOAA’s official outlook for March through May — an outlook influenced significantly by El Niño’s lingering ways — looks quite a bit different from The Weather Channel’s:

NOAA’s temperature outlook for March through May shows warmer than average conditions for much of the northern portion of the contiguous United States. (Credit: NOAA Climate Prediction Center)

The graphic shows that for a very large part of the contiguous United States, whether it will be warmer or cooler than average essentially comes down to a coin flip. But the exception is the northern tier.

The warmth in the north forecast by NOAA is typical with El Niño, particularly a strong one like we’ve been experiencing.

Why You Should Care

If you’re wondering why it’s worth paying attention to any of this, you might ask yourself whether you care about, well, the weather.

El Niño and La Niño are two sides of a climatic coin known as the El Niño Southern Oscillation, or ENSO. And they both make certain weather patterns more or less likely.

In the case of El Niño, it starts with warmer than average sea surface temperatures in large parts of the tropical Pacific Ocean. Through a complex chain of events, that tends to lead to the strongest parts of the jet stream shifting southward and extending farther eastward across the North Pacific Ocean, according to Emily Becker, Associate Director of the University of Miami’s Cooperative Institute for Marine and Atmospheric Studies. In so doing, the strongest part of the jet moves closer to North America, helping to steer storms across the southern third.

The jet stream pattern during El Niño winters, shown as the average west-east wind for all El Niño winters 1959–2023. Shading and arrows indicate the wind speed. Positive values show winds from the west, whereas negative values indicate easterlies. During El Niño, the core of the jet stream extends farther eastward over the Pacific compared to La Niña winters. (Credit: NOAA Climate.gov image from NCEP/NCAR Reanalysis data and analysis by Michelle L’Heureux.)

These changes, in turn, can help boost the frequency, strength and persistence of atmospheric rivers, contributing to the kind of extreme precipitation California has been experiencing this winter — including right now.

But El Niño is already fading, and La Niña seems to be coming, right? So what’s up with that?

“Impacts on North American temperature and precipitation tend to linger after the peak of El Niño,” Becker told me in an email. This is true for temperature too. “El Niño is related to warmer-than-average conditions across the northern half of the U.S. through the spring.”

El Niño’s lingering impact is why forecasters feel confident in saying the odds favor continuing warmth during spring in the north. And don’t be surprised if there is even more extreme precipitation to come in California.

Odds, Not Certainty

That said, just because certain weather patterns are more likely doesn’t mean they are inevitable. Our results may vary, depending on random throws of the weather dice.

Moreover, the transition is expected to be fairly quick, heightening uncertainty in forecasts of weather impacts. That’s because it’s very challenging to predict the exact timing of El Niño’s final demise.

“Yes, El Niño is waning and La Niña is expected to develop this summer, but it’s even more difficult than usual to predict seasonal temperature and precipitation patterns during the transition between phases, because neither phase is in charge,” Becker said in her email to me.

Why, then, are forecasters so very confident that El Niño wil leave the stage? This animation helps provide an answer:

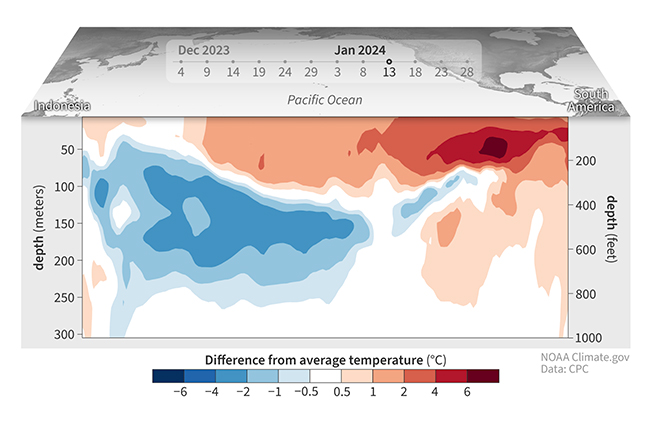

Water temperatures between December 2023 and January 2024 in the top 300 meters (1,000 feet) of the tropical Pacific Ocean, compared to the 1991–2020 average. (Credit: NOAA Climate.gov animation, based on data from NOAA’s Climate Prediction Center.)

The animation, covering December through January, shows the evolution of sea temperatures in a 300 meter (~1,000 foot) cross section of the Pacific Ocean along the Equator. As indicated by the orange and red colors, above-average temperatures persist at and near the surface in the central and eastern equatorial Pacific. This is a hallmark of El Niño.

But as the animation also shows, a chilly phantom is rising from the depths and expanding eastward, threatening to replace the warm water: a truly enormous blob of cooler-than-average ocean waters. This is one of the main reasons scientists are forecasting a nearly 80 percent chance that El Niño will fade to neutral during the April through June period, with a 55 percent chance that La Niña will take charge during June through August.