Earth Just Had its 15th Straight Month of Record Setting Temperatures

Posted on Categories Discover Magazine

Our planet still can’t seem to beat the heat.

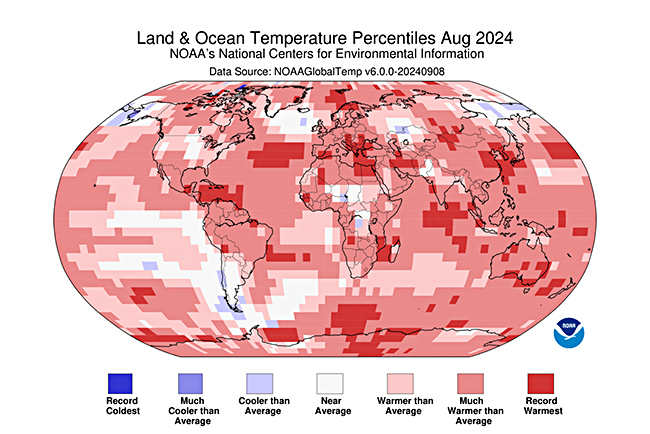

Last month was the warmest August on record. “Sweltering” was the word used by the normally staid National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration to sum up the findings of its regular monthly analysis.

And August wasn’t just a one-off. By NASA’s independent calculation, last month caps the hottest summer in the Northern Hemisphere since global record-keeping began in the 1800s. It also extends our planet’s heat streak to 15 straight months of record setting global temperatures.

This bar graph shows how summer global temperatures in 2023 (in yellow) and 2024 (in red) varied from the long-term average. (The white lines indicate the range of estimated temperatures.) These warmer-than-usual summers continue a long-term trend of warming, driven primarily by human-caused greenhouse gas emissions. (Credit: NASA/Peter Jacobs)

June, July and August of 2024 — meteorological summer in the Northern Hemisphere — together were 2.25 degrees F (1.25 C) warmer than the average summer between 1951 and 1980, according to NASA. August alone was 2.34 F (1.3 C) warmer than average. Most concerning, the heat has been continuing even as the warming influence of the strong El Niño of 2023 and 2024 has faded.

“Data from multiple record-keepers show that the warming of the past two years may be neck and neck, but it is well above anything seen in years prior, including strong El Niño years,” says Gavin Schmidt, director of NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies “This is a clear indication of the ongoing human-driven warming of the climate.”

Given what we’ve already seen this year, 2024 will almost certainly go down as the warmest year on record,” Schmidt predicted recently.

One impact of the extraordinary level of warming is likely being felt in the western United States, where multiple large wildfires are burning. Southern California has been particularly hard hit, where three vicious blazes have burned more than 100,000 acres in a short period of time.

This timelapse video showing the Line Fire raging near San Bernardino drives home the severity of what’s happening:

Since 1980, California has seen a significant long-term trend of higher temperatures and drier air. These conditions are, of course, conducive to wildfire. And in fact, research shows that due to our influence on the climate, wildfire has been consuming more and more Golden State acreage in recent decades. For example a study published last year found a 320 percent increase in burned areas between 1996 to 2021 — with nearly all of the increase attributable to human-caused climate change.

An Alarming Mystery

Zooming back out to the global level, scientists have been puzzled by the persistent heat.

“Unfortunately, we still lack a good explanation for what drove the exceptional warmth the world saw in 2023 and 2024,” says Zeke Hausfather, a climate scientist with the Breakthrough Institute, writing in his Climate Brink newsletter. Scientists have considered a host of “potential mediocre explanations,” including a volcanic eruption, changes in solar activity, and El Niño behaving weirdly. “But these have increasingly been modeled, and it is hard to explain the magnitude of the global temperature anomaly the world has experienced even adding all of these estimates together.”

Moreover, even as El Niño has faded, and its cooling sibling, La Niña, has loomed, the record-setting warmth has shown no definitive signs abating, defying expectations.

This graph shows estimates of daily surface air temperatures globally from 1984 through Sept. 9, 2024. Temperatures since Sept. 1 of this year have been warmer or nearly so than last year at this time — when daily records were being set. (Credit: Climatereanalyzer.org)

The mystery of what’s going on has alarmed some scientists. Had global temperatures eased, it would have suggested that the record scorching was just “a blip — some short lived internal variability that drove a spike in global temperatures but did not persist,” Hausfather says.

Although there’s some scientific debate about this, a “blip” is looking less and less likely. Even now, into September, temperatures have remained at or near record-setting territory. That means “it’s looking increasingly less likely that last year’s elevated temperatures were a mostly transient phenomenon,” Hausfather says.

This could mean that positive feedbacks — in which warmth triggers changes that encourage still greater warmth — “may be driving higher global temperatures going forward.”

You could be forgiven for feeling a sense of doom given the abiding mystery, and the possibility that we may have entered a dangerous, self-reinforcing climate regime. But Andrew Dessler, Director of the Texas Center for Climate Studies at Texas A&M University, says we need to resist despair, saying in his own newsletter: “Please don’t feel this way!”

Cause for optimism

Dessler cites two facts that keep keep him grounded. The first is that the climate will stop warming as soon as humans stop emitting greenhouse gases into the atmosphere. And if that seems like a remote possibility, he also notes that the technology needed to mostly stop emissions over the next few decades is already available.

In fact, it’s already helping quite a lot.

“We are living through a legitimate, once-in-a-lifetime energy revolution,” Dessler says. “The last one was 150 years ago when the fossil-fuel era started. Today, we’re moving from that energy system, which is based on burning crap, to one based on directly generating electricity from renewable energy sources.”

As I’ve written recently, CO2 emissions from the United States and other advanced economies fell 4.5 percent last year. Outside of a recessionary period, the world has never seen such a substantial decline. Moreover, this occurred even as gross domestic product jumped by 1.7 percent.

This shows Dessler is right: We absolutely know how to drive emissions down, and we’ve begun doing it.

But to avert even hotter and more devastating years than what we’ve been living through, the advanced economies must accelerate their move away from “burning crap” and toward zero-carbon, renewable energy sources. They must also help other nations to do the same.

We’re all in this together, and it’s time that we finish the energy revolution that is already underway — before it’s too late.