As Earth Sizzles, CO2 in the Atmosphere Accelerates Faster Than Ever

Posted on Categories Discover Magazine

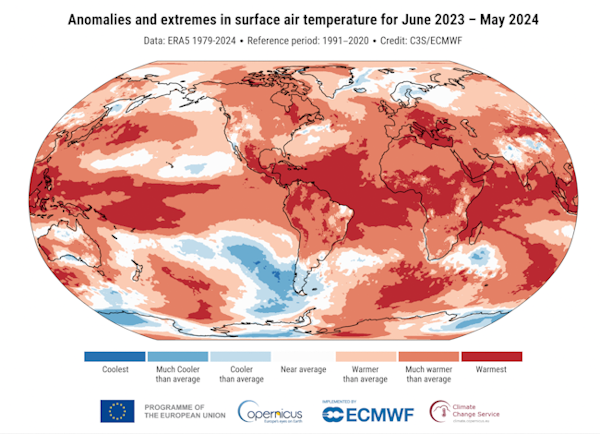

The first of several global heating analyses for May is in, and while expected, the news, from the Copernicus Climate Change Service, is still disturbing:

It was the warmest May on record, continuing a record-setting heat streak that has now lasted for each of the past 12 months, going back to June 2023.

This means global temperatures have been at 1.63 degrees C above preindustrial levels over the past 12 months, according to the Copernicus analysis. Under the Paris Agreement, countries agreed to restrain the increase of global average surface temperature to 1.5 C.

This short-term warming doesn’t mean we’ve breached that threshold — which concerns a longer-term span of years, not months. Nonetheless, ”we are way off track to meet the goals set in the Paris Agreement,” says Ko Barrett, deputy-secretary of the World Meteorological Organization. “We must urgently do more to cut greenhouse gas emissions, or we will pay an increasingly heavy price in terms of trillions of dollars in economic costs, millions of lives affected by more extreme weather and extensive damage to the environment and biodiversity.”

Unfortunately, the level of heat-trapping carbon dioxide in the atmosphere continues to accelerate, scientists from NOAA and the Scripps Institution of Oceanography announced yesterday.

Carbon dioxide’s relentless rise in the atmosphere continues: In May it reached its peak for the year at just shy of 427 parts per million — the highest level in millions of years. (Credit: NOAA Global Monitoring Laboratory)

“Not only is CO2 now at the highest level in millions of years, it is also rising faster than ever,” says Ralph Keeling, Director of the CO2 Program at Scripps, quoted in a release. “Each year achieves a higher maximum due to fossil-fuel burning, which releases pollution in the form of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. Fossil fuel pollution just keeps building up, much like trash in a landfill.”

Measured atop Hawaii’s Mauna Loa, CO2 reached its annual high in May at a little less than 427 parts per million. That’s 2.9 ppm greather than in May 2023. “When combined with 2023’s increase of 3.0 ppm, the period from 2022 to 2024 has seen the largest two-year jump in the May peak in the NOAA record,” according to the agency.

Rays of Hope

The CO2 surge will continue until we more vigorously restrain out gusher of emissions. And here is where we might actually find one ray of hope:

In the last decade, the growth in humankind’s emissions of carbon dioxide has slowly declined. The growth rate between 2013 and 2022 averaged 0.5 percent per year, down from a peak of 3 percent per year, according to Global Carbon Budget 2023, a detailed paper published at the end of last year.

If you’re wondering how the level of CO2 in the atmosphere can still be accelerating even as our emissions of CO2 to the atmosphere are slowing and perhaps even leveling off, that’s a great question! Part of the answer is likely to be the strong El Niño that began in June 2023 and is only now nearly gone. The climate phenomenon limits uptake of atmospheric CO2 by land ecosystems, according to John Miller, a carbon cycle scientist with NOAA’s Global Monitoring Laboratory.

But I suspect there’s more to this, so I’m hoping to explore the issue in more detail in a future column.

In the meantime, it’s important to keep in mind something the authors of the Global Carbon Budget Paper emphasized: While the slowdown in the amount of carbon dioxide we’re pumping into the atmosphere is indeed good news, “global fossil CO2 emissions continue to grow and are far from the rapid decreases needed to be consistent with the temperature goals of the Paris Agreement.”

But here, too, there is a ray of hope: In its World Energy Outlook 2023 report, the International Energy Agency projects that CO2 emissions from energy use and industry will peak in the mid-2020s. In fact, pending further analysis of the numbers, the IEA says it may have actually happened last year.

If we can speed up our decarbonization efforts by accelerating the transition away from fossil fuels and curbing such land-use practices as deforestation, we still have time to avoid the most dire impacts of climate change.

Or as author and climate scientist Michael Man has written, “There is urgency in reducing carbon emissions. But there is also still agency on our part in acting.”