AI Could Translate 5,000-Year-Old-Language, Saving Time and Historical Insights

Posted on Categories Discover Magazine

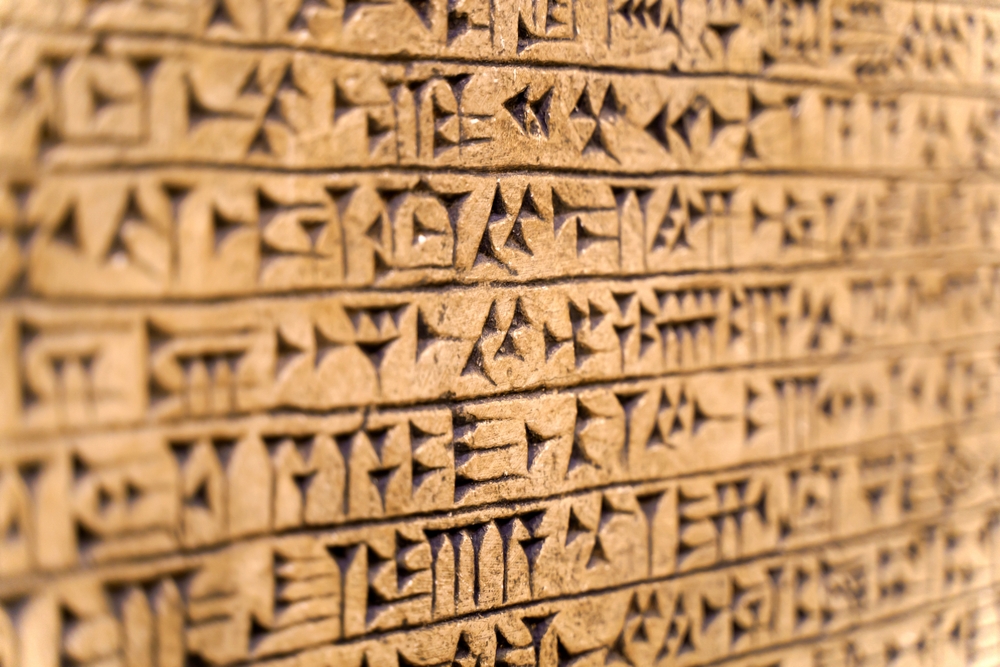

Tens of thousands of cuneiform tablets are sitting around, just waiting to be translated. It’s not an easy job; the ancient language is based on wedge-shaped pictograms and includes more than 1,000 unique characters that vary by era, geography, and individual writer.

But decoding the pictograms could be a culturally and historically significant task. Cuneiform arose about 5,000 years ago in Mesopotamia, in what is now Iraq. It is one of four known pristine languages — writing systems with no known influences from any other. Some translated cuneiform tablets have revealed contents as banal as a record of inventory for shipping. Others have been more profound — like the “Epic of Gilgamesh,” the first known written work of literature.

Those translations, done by a relatively few individuals who know the language, required a lot of labor — and perhaps some guesswork. Decoding such complexity would be the perfect job for artificial intelligence, thought some Cornell University researchers, who, with colleagues at Tel Aviv University, created a system to do just that, they report in a paper to be presented at an April 2025 conference.

AI Deciphers Ancient Tablets

The research team developed a system that overcomes the many obstacles that variations present to translation.

“When you go back to the ancient world, there’s a huge variability in the character forms,” Hadar Averbuch-Elor, a Cornell computer science professor who led the research, said in a press release. “Even with the same character, the appearance changes across time, and so it’s a very challenging problem to be able to automatically decipher what the character actually means.”

The computer system reads photographs of clay cuneiform tablets, then adjusts by computationally overlaying the images atop ones with similar features, and whose meaning is known. Because the system automatically aligns the two images until they digitally click into place, they named the system ProtoSnap.

Read More: Could AI Language Models Like ChatGPT Unlock Mysterious Ancient Texts?

What We Can Learn From Ancient Texts

In the paper, the researchers demonstrated that the snapped characters can be used to train the system to see other similarities between other characters later in the process, what they call downstream. When the system received such training, ProtoSnap performed much better at recognizing cuneiform characters — even rare ones or characters with lots of differences — than previous AI efforts.

This advance could help automate the tablet-reading process. This would save an enormous amount of time. It could also help scholars better compare writings from different times, cities, and authors. But most importantly, it would dramatically hasten the translation process — ultimately giving the world access to an abundance of ancient writing.

“The base of our research is the aim to increase the ancient sources available to us by tenfold,” Yoram Cohen, a co-author and archaeology professor at TAU said in the press release. “This will allow us, for the first time, the manipulation of big data, leading to new measurable insights about ancient societies – their religion, economy, social and legal life.”

Although many translated tablets will likely just show, say, a receipt for a livestock purchase, others could contain fascinating historical accounts — or even another epic poem.

Article Sources

Our writers at Discovermagazine.com use peer-reviewed studies and high-quality sources for our articles, and our editors review for scientific accuracy and editorial standards. Review the sources used below for this article:

Before joining Discover Magazine, Paul Smaglik spent over 20 years as a science journalist, specializing in U.S. life science policy and global scientific career issues. He began his career in newspapers, but switched to scientific magazines. His work has appeared in publications including Science News, Science, Nature, and Scientific American.