A Tiny, Extinct Mammal Has Just Lost Its Primate Identity

Posted on Categories Discover Magazine

A new look at the skull of a tiny extinct mammal has revealed to researchers that it did not belong to the primate order as previously thought, reversing a decades-long notion about the identity of this elusive mammalian family, known as “picrodontids.”

Mouse-sized picrodontids, living several million years after the extinction of dinosaurs, were placental mammals that likely lived on a diet of fruit, nectar, and pollen. Until now, they were envisioned as primates because of their teeth, which share features with the teeth of living primates. A research paper published in Royal Society’s Biology Letters has now dispelled this idea and designated picrodontids as separate from primates.

How Do We Know Picrodontids Are Not Primates?

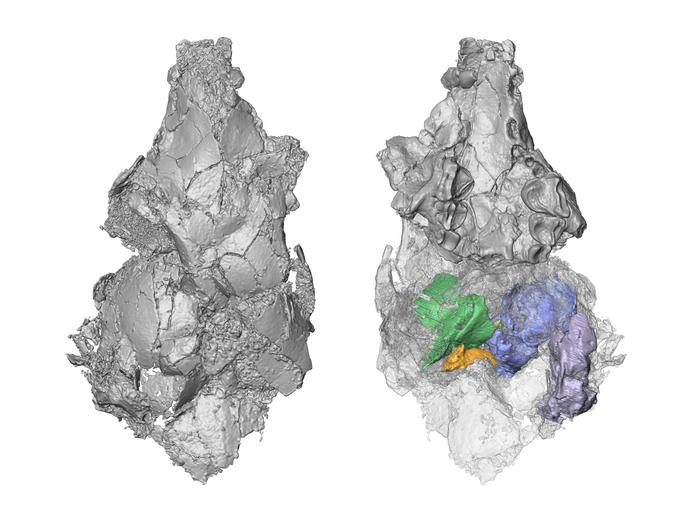

According to a press release statement, this revelation came to light when Jordan Crowell, an anthropology Ph.D. candidate at the CUNY Graduate Center and lead author on the paper, used modern CT scan technology to analyze the only known preserved picrodontid skull in Brooklyn College’s Mammalian Evolutionary Morphology Laboratory. Crowell worked with his Ph.D. adviser, anthropologist Stephen Chester, and John Wible, Curator of Mammals at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History, to verify that picrodontids are not closely related to primates after all.

“While picrodontids share features of their teeth with living primates, the bones of the skull, specifically the bone that surrounds the ear, are unlike that of any living primate or close fossil relatives of primates,” Crowell says. “This suggests picrodontids and primates independently evolved similarities of their teeth for similar diets. This study also highlights the importance of revisiting old specimens with updated techniques to examine them.”

The Evolution of Picrodontid Classification

The same skull, given the name Zanycteris paleocenus, was central to the initial classification of picrodontids by paleontologist Frederick Szalay, who was a colleague of Chester. Szalay studied the skull’s fossilized teeth and concluded in 1968 that they aligned with primate teeth based on the similarities.

With CT scan technology, the paper’s authors could perceive a clearer picture of the skull and update earlier judgments of picrodontids.

“The Zanycteris cranium was prepared and partially submerged in plaster around 1917, so researchers studying this important specimen at the American Museum of Natural History were not aware of how much cranial anatomy was hidden over the last 100 years,” Chester says. “Micro-CT scanning has revolutionized the field of paleontology and allows researchers to discover so much more about previously studied fossils housed in natural history museum collections.”

Read More: Mammals Diversified Much More Rapidly 66 Million Years Ago

Observing Mammalian Species

Mammals are divided into three groups: placentals, marsupials, and monotremes. Differences in reproduction separate the groups.

Most mammalian species — humans included — are placentals, categorized as such because they have a placenta, an organ that forms after conception and provides nutrients to the fetus. As a placental mammal, picrodontids would have given live birth to well-developed young.

The Cretacious Extinction and and the Rise of Placental Mammals

Most orders of placental mammals likely originated after the Cretaceous-Paleogene (K-Pg) extinction event, occurring 66 million years ago when a giant asteroid crashed into Earth and caused the death of about 75 percent of all species. Having lived after dinosaur extinction, picrodontids would probably fall into the category of placentals that appeared following the K-Pg event.

Evolutionary Insights from Fossilized Teeth

A 2023 study published in Current Biology found that four of the orders evolved right before the extinction event and co-existed with dinosaurs. The study observed 100 percent support for a Cretaceous origin of primates. Also showing high support for a Cretaceous origin were three other orders: Eulipotyphla (shrews and moles), Lagomorpha (rabbits), and Carnivora (dogs, cats, bears).

Going back even further, all mammals descended from a common ancestor. That title is currently held by Brasilodon quandrangularis, a shrew-like creature that existed 225 million years ago. Brasilodon, identified from fossilized dental records, possessed two successive sets of teeth: the first developed during the embryonic stage and the second developed after birth.

Read More: What Was the End-Cretaceous Mass Extinction?

The Role of Diet in Mammalian Evolution

A species’ diet correlates with its anatomical features, as shown in Charles Darwin’s famous observation of varying beak sizes in Galápagos finches. Primates follow this pattern as well, with certain species developing different dental structures based on what they eat.

Primates’ teeth have adapted to consume a wide variety of food. They have incisors (front teeth for biting off pieces of food), canines (for tearing), and premolars and molars (for grinding). Humans also have all these teeth, but ours are much smaller and duller. We do have one advantage over some primates: our molars have a thicker layer of enamel that ensures better grinding and protects the teeth.

The Significance of Tooth Shape

The mechanical functions needed to digest certain foods plays a major role in primate tooth shape, particularly in molars. Primates that are insectivores or folivores (leaf-eating) have higher crowned teeth that help them chew fibrous material, while frugivore (fruit-eating) and hard-object-eating primates have lower crowned teeth that help them exert strong bite forces.

Fossilized teeth are crucial for the research conducted by many paleontologists. They are one of the best preserved parts of a body, have proved effective in studies of ancient DNA, and give valuable insight on the diets of prehistoric humans and extinct animals like picrodontids.