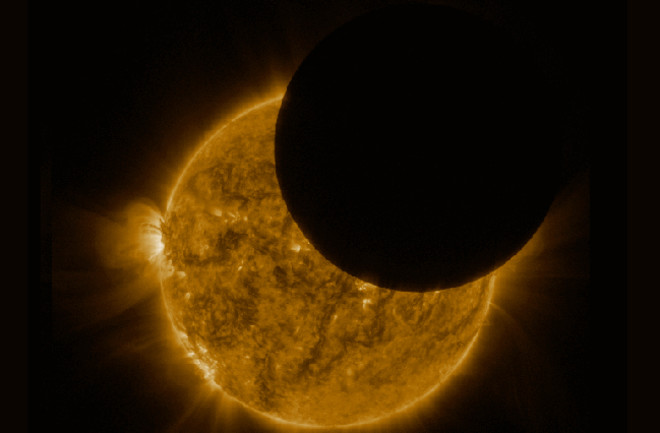

A Solar Eclipse, as Seen by a Spacecraft Orbiting 22,000 Miles Away

Posted on Categories Discover Magazine

As the orb of the Moon transited in front of the Sun on Nov. 13, 2023, the Solar Ultraviolet Imager, or SUVI, aboard the GOES East satellite captured this image of the resulting partial solar eclipse. For a video of the event, see below. (Credit: Cooperative Institute for Meteorological Satellite Studies)

Back in October, tens of millions of people in the Western Hemisphere witnessed a rare “ring-of-fire” annular solar eclipse that elicited cheers and shouts of joy. But when another dramatic eclipse occurred just one month later, there was no fanfare.

That’s because no one here on Earth was able to witness it live.

As seen in the image above, and in the animation directly below, it occurred when the New Moon transited across the face of the Sun on Nov. 13, causing a partial eclipse. The compelling imagery comes to us from the GOES East satellite, located in geostationary orbit.

The Moon’s orb transits the Sun on Nov. 13, 2023, as seen by the GOES East satellite. (Credit: CIMSS Satellite Blog)

Why was the event visible to the satellite but not to anyone here on Earth?

Solar eclipses can be viewed from Earth only when the Moon glides into just the right position between us and the Sun. At this time of the New Moon, our natural satellite’s sunlit side faces away from us, so its surface is pitch dark. And the Moon casts a shadow across the surface of the Earth, eclipsing the view of the Sun.

But not every New Moon can produce an eclipse. That’s because the Moon’s orbit is tilted slightly with respect to our orbit around the Sun. And as the the animation above shows, this tilt causes the Moon’s shadow to miss the Earth. This happens during roughly five out of six New Moons.

But during two “eclipse seasons” each year, the New Moon’s path intersects what’s known as the Sun-Earth ecliptic plane. When this happens, the Moon’s shadow can reach Earth’s surface and cause an eclipse.

Meanwhile, geosynchronous satellites, which orbit about 22,000 miles above the equator, can pass through the Moon’s shadow during an eclipse season even when that shadow cannot reach Earth. And that’s precisely what happened on Nov. 13.

A Solar Eclipse Seen in Extreme Ultraviolet Light

The partial eclipse was seen by a telescope aboard the GOES East satellite called the Solar Ultraviolet Imager, or SUVI. The extreme UV light that SUVI is designed to detect is produced in the Sun’s blistering hot outer atmosphere, called the corona. Thanks to absorption in the atmosphere, that light doesn’t reach Earth’s surface. But from SUVI’s perch aboard a GOES satellite in geostationary orbit, the telescope is able to see it clearly. That allows SUVI to provide early detection of solar flares and coronal mass ejections that can disrupt communications and electrical transmission systems on Earth.

GOES satellites are actually best known for their imagery of Earth. In fact, they make up the Western Hemisphere’s most sophisticated weather-observing and environmental-monitoring system. So when October’s ring-of-fire eclipse occurred, the GOES East spacecraft was able to provide an awesome view of the Moon’s shadow sliding across a broad swath of North, Central and South America. Check it out in the video above.