A Prehistoric Giant Salamander With Fangs May Redraw an Evolutionary Picture

Posted on Categories Discover Magazine

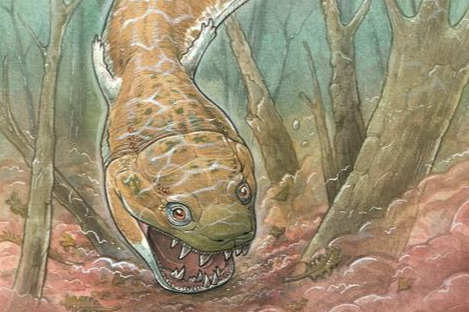

Picture an amphibian over 6 feet long, with a suction-cup mouth containing 4-inch fangs in a 2-foot-long skull that holds a ring of smaller, but equally sharp teeth.

Such a creature dominated the waters 40 million years before dinosaurs usurped it as a top predator and comes from a lineage once thought to be extinct millions of years before its aquatic reign. This creature, Gaiasia jennyae — which could aptly be named “salamander from hell” — is described in a new report in Nature.

“Gaiasia jennyae was considerably larger than a person, and it probably hung out near the bottom of swamps and lakes,” Jason Pardo, a postdoc at the Field Museum in Chicago and co-lead author study, said in a statement. “It’s got a big, flat, toilet seat-shaped head, which allows it to open its mouth and suck in prey. It has these huge fangs, the whole front of the mouth is just giant teeth.”

Ambush Amphibian

G. jennyae’s physical characteristics rendered it a fearsome and effective aquatic predator.

“Gaiasia has a flat head that’s good for suction and large fangs that are good for grabbing and killing prey, but that wide flat head wouldn’t have been very hydrodynamic,” says Pardo.

These features and other physiological characteristics meant that the ancient giant salamander likely hid, then ambushed its prey, because it probably lacked the speed of other predators.

“Fast ambush predators like pike or gar tend to have long, narrow faces which can move more quickly through the water; that’s not what we see in Gaiasia,” says Pardo.

Read More: These Ancient Amphibians Were as Massive as Hippos

Ancient Giant Salamander Evolution

The G. jennyae finding is not just notable because of its ferocity, but because it appears to be a holdover from a group called stem tetrapods — early four-legged vertebrates that branched out into other lineages that would eventually lead to mammals, reptiles, and amphibians. The G. jennyae fossils clearly connect to this group.

“Gaiasia still has a lot of bones and other structures that are lost by the time we see the lineages leading to modern amphibians, reptiles, and mammals,” says Pardo. “This is important because we have thought for a long time that animals like Gaiasia had gone extinct tens of millions of years earlier, either from climate change or from competition with more advanced tetrapod groups. Gaiasia is making us reconsider these ideas.”

Why Gaiasia persisted when other stem terapods faded into evolutionary oblivion remains a mystery that is open to speculation. The location of the fossil Namibia, just north of South Africa, could offer some clues.

That location was even further south 300 million years ago — almost then with the present northernmost point of Antarctica. Even though swamp land near the equator was rapidly drying up during the Permian Period, swamps and lakes possibly remained in patches alongside ice and glaciers closer to the poles.

“Maybe stem tetrapods like Gaiasia were better at handling cold temperatures than more advanced tetrapods,” says Pardo. “Or maybe animals like Gaiasia were actually successful across a lot of the planet but weren’t adapted to the heat at the equator, and it just happens that our understanding of this time interval is biased towards a very small equatorial region. Or maybe something else entirely. It’s hard to know without more fossils.”

Read more: How Giant Salamanders Stretch to Such Enormous Sizes

Article Sources

Our writers at Discovermagazine.com use peer-reviewed studies and high-quality sources for our articles, and our editors review them for accuracy and trustworthiness. Review the sources used below for this article:

Before joining Discover Magazine, Paul Smaglik spent over 20 years as a science journalist, specializing in U.S. life science policy and global scientific career issues. He began his career in newspapers, but switched to scientific magazines. His work has appeared in publications including Science News, Science, Nature, and Scientific American.