Volcanic Blasts May Be to Blame for Strange Blue Rings in Norway’s Trees

Posted on Categories Discover Magazine

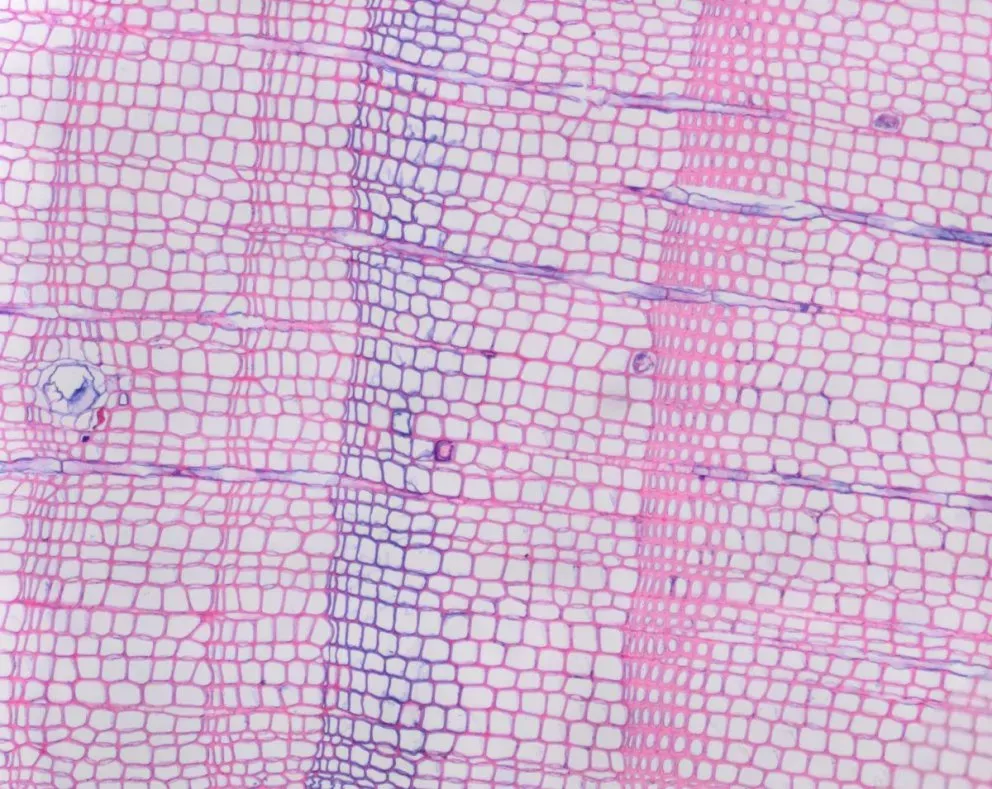

Human skin isn’t the only thing that can change color after facing the cold. Trees and shrubs change colors, too, taking on a special blue tinge after they are sampled and stained. That’s according to a new study in Frontiers in Plant Science, which found strange blue rings in samples of trees and shrubs from the northern treeline in Norway.

“Blue rings look like unfinished growth rings, and are associated with cold conditions during the growing season,” said Agata Buchwal, a study author and dendrochronologist at Adam Mickiewicz University in Poland, in a press release.

In fact, the study authors say that their findings testify to two cold seasons almost 150 and 125 years ago, perhaps caused by a pair of volcanic eruptions.

Read More: What Causes Volcanic Eruptions: Can We Predict Them?

Summertime Struggles for Norway’s Trees and Shrubs

Trees and shrubs struggle to grow when their summertime growing seasons are cold. That’s because the cell walls of their growing cells can’t solidify in cold conditions, creating weakened wood rings that turn blue when the wood is sampled and stained. Since trees and shrubs live long lives, some as many as thousands of years, scientists can pinpoint the past’s chilliest summers by searching for these blue rings.

Selecting Mount Iškoras in Norway for a search for blue rings, a team of researchers took samples from 25 pine trees and 54 juniper shrubs, representing the species Pinus sylvestris and Juniperus communis, at the northern tree limit. After slicing and staining their samples, the researchers then slid them under a microscope to measure their growth rings, as well as their blue rings.

All told, the researchers found that around 84 percent of their pine tree samples and 36 percent of their juniper shrub samples showed blue rings in 1877, while around 96 percent of their pine trees and 68 percent of their juniper shrubs showed blue rings in 1902.

Sifting through the weather records from the Mount Iškoras weather station, the team confirmed that the summers of 1877 and 1902 were cold, with the coldest temperatures in August 1877 and June 1902, and potentially tied to a pair of volcanic eruptions. While the blue rings from 1877 align with a June eruption of Cotopaxi in Ecuador, the blue rings from 1902 align with a May eruption of Mount Pelée in Martinique.

Read More: 5 of the Most Explosive Volcanic Eruptions

A Cold Connection to Volcanism

Mostly observed in latewood, which grows in the summertime season, 2.1 percent of the pine trees’ growth and 1.3 percent of the juniper shrubs’ growth turned blue after staining. This suggests that pine trees are more susceptible to cold conditions, and thus more sensitive indicators of summertime cold.

“In general, we found more blue rings in trees than in shrubs,” Buchwal said in the release. “Shrubs seem to be more adapted to cooling events than trees, which is probably why shrubs are found further north.”

While beneficial to scientists today, blue rings aren’t a boon for the trees and shrubs that contain them.

“Blue rings have the potential to weaken the tree, making it more susceptible to mechanical damage or disease,” said Pawel Matulewski, another study author and dendrochronologist at Adam Mickiewicz University, in the release. “If this phenomenon persists over several years, it can impede the tree’s recovery.”

While other studies suggest connections between blue rings and volcanism, additional research is needed to tie the blue rings at the northern treeline to Cotopaxi and Mount Pelée. Indeed, no other research reveals a correlation between the summertime cold in Norway in 1877 and Cotopaxi, and the temperatures in both 1877 and 1902 could be linked to another component of the climate, instead.

According to the team, complete, consistent temperature recordings are necessary for this additional research. While limited temperature recordings restricted the researchers’ ability to confirm other cold summers in Norway, a lack of recordings at the specific location of the trees and shrubs limited their ability to confirm the temperatures that afflicted them.

“We hope to inspire other research groups to look for the blue rings in their material,” Buchwal said in the release. “It would be great to establish a blue ring network based on trees and shrubs to reconstruct cooling events at the northern treeline over long timescales.”

Read More: 5 Things You Might Not Know About Volcanoes

Article Sources:

Our writers at Discovermagazine.com use peer-reviewed studies and high-quality sources for our articles, and our editors review for scientific accuracy and editorial standards. Review the sources used below for this article:

Sam Walters is a journalist covering archaeology, paleontology, ecology, and evolution for Discover, along with an assortment of other topics. Before joining the Discover team as an assistant editor in 2022, Sam studied journalism at Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois.