What Education Looked Like for These 5 Ancient Societies

Posted on Categories Discover Magazine

Today, kids are expected to spend much of their day in school. Learning is divided into grades and separated by age and aptitude. But it hasn’t always been this way. Education wasn’t always required, and in fact, many kids carried on the jobs their parents had instead of learning how to read and write. What and how one learned depended on one’s place in society.

In ancient times, much like today, education was highly valued. Subjects could range from reading and writing to philosophy and ethics. There have only been a few pieces of evidence to help us understand how ancient people taught their children. But we do know what they were taught and who in society had access to the teachings. Here’s what education looked like in these five ancient societies.

1. Mesopotamia

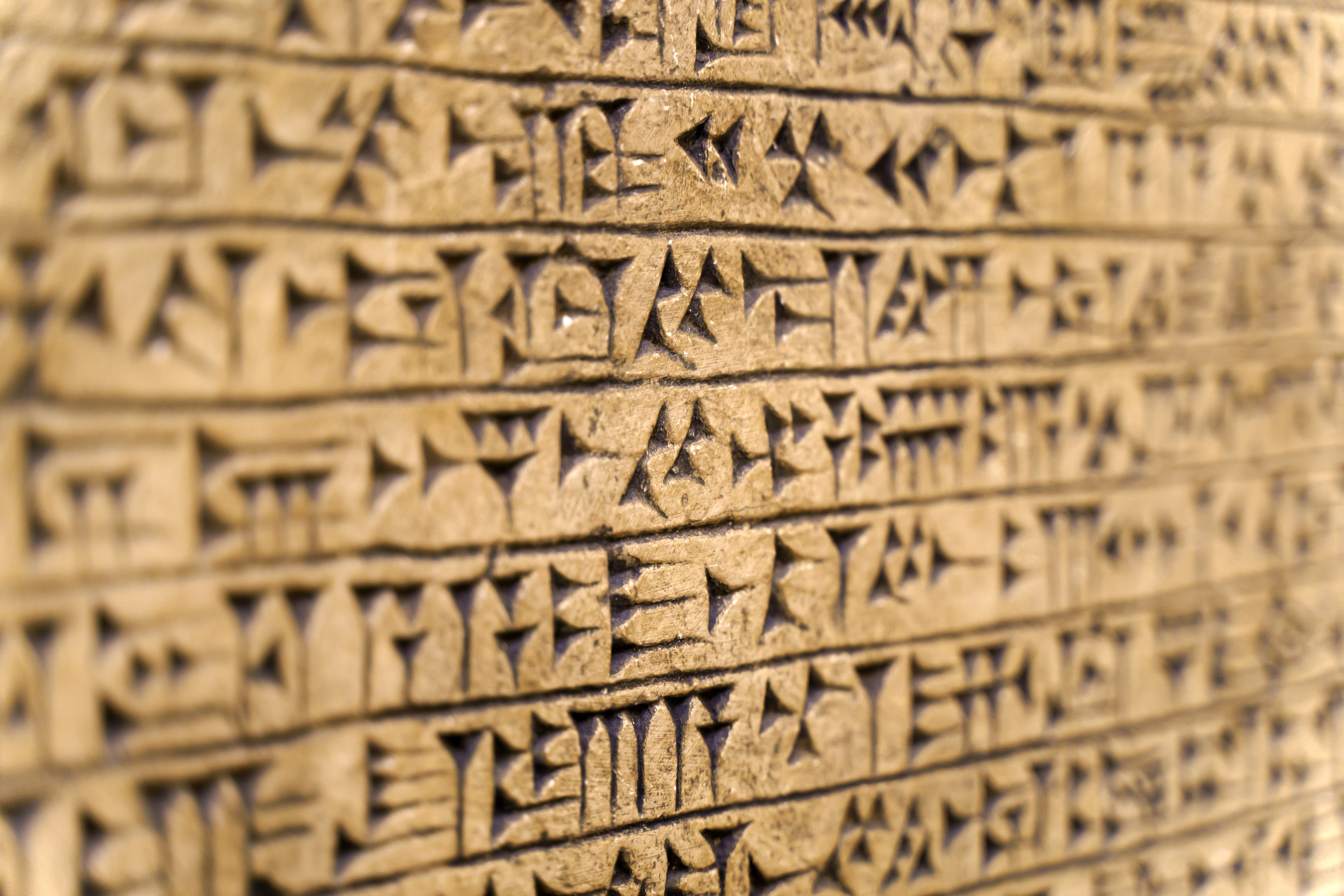

Records of learning in ancient societies are scarce, depending on the society that you’re referring to. But researchers have unearthed some evidence. Tablets from ancient Mesopotamia show that kids wrote on ancient clay tablets the way that one might write on a chalkboard today.

Kids learned cuneiform, an ancient writing system, by transcribing what the teacher wrote and then erasing what was written and starting again. Researchers have found around 600 tablets with imperfect, childlike forms of the language written on them.

2. Ancient Egypt

With regards to ancient Egypt, there’s a lot we don’t know because we don’t have a record of it, says Aidan Dodson, an Egyptologist and historian at the University of Bristol. We know that only a tiny portion of the population were educated to read or write, and these were likely the sons and maybe daughters of those who could already read and write.

“There are no documents to show how they learned,” says Dodson. But much of what survives are school children’s copies of other works, an indication that children learned by dictation with the student copying what a teacher said or wrote. Beyond that, much of the population would have learned a vocation, apprenticing to do what their father or mother did as a profession.

3. Ancient Rome

According to the ancient educator Quintilian, who lived in the first century A.D., going to school was better than home education because children benefited from the social interaction of studying with other students.

School would have started around age 7 and though students were mostly male, some girls did attend, though they wouldn’t have gone as far in their studies because most would marry in their early teenage years. Students would have sat on the floor rather than at desks and they wouldn’t have been separated by grade and skill level, like today.

4. Zhou Dynasty

During the Zhou dynasty in China from 1046 B.C. until 256 B.C., much of the schooling was likely done in village and district schools where young students learned to read and write using bamboo books. The education was secular-focused and emphasized ethics.

Education was considered an individual pursuit marked by moral excellency and only the students who did the best in school would have proceeded to higher education. Jixia Academy, which was started in 360 B.C., was made up of 100 schools which included regular lectures on an assortment of topics geared towards men.

5. The Incas

The Incan Empire, which existed from 1200 A.D. to 1533 A.D., learned through oral tradition. Most of the population would have learned a vocation instead of academics.

The exception was the nobles who had a more organized education system that was separated into four years. The first year, students would have learned the Quechua language, which was largely spoken by the elites. Then they would have learned quipu, the ancient art of knotting, as well as spending ample time studying religion. And the final year would have been spent studying things like history, astronomy, geography, and the sciences.

Amautas, the professional teachers of the Incan empire, taught students. These elite students would have had to complete an examination at the end of their studies to attain their education.

Read More: 7 Groundbreaking Ancient Civilizations That Influence Us Today

Article Sources

Our writers at Discovermagazine.com use peer-reviewed studies and high-quality sources for our articles, and our editors review for scientific accuracy and editorial standards. Review the sources used below for this article:

Sara Novak is a science journalist based in South Carolina. In addition to writing for Discover, her work appears in Scientific American, Popular Science, New Scientist, Sierra Magazine, Astronomy Magazine, and many more. She graduated with a bachelor’s degree in Journalism from the Grady School of Journalism at the University of Georgia. She’s also a candidate for a master’s degree in science writing from Johns Hopkins University, (expected graduation 2023).