Is Tabby’s Star a Swarm of Extraterrestrial Structures?

Posted on Categories Discover Magazine

In 2016, word came out about the discovery of a downright strange astrophysical object, somewhere in the constellation Cygnus. It wasn’t another Earth, but rather, a star.

Citizen scientists had been combing through the data from four years of NASA’s Kepler mission when they encountered the star, officially named KIC 8462852. And it was an oddball. It randomly dimmed, like a flickering lightbulb, and could stay that way for several days. It fluctuated intensely and erratically, sometimes dropping up to 22 percent in brightness.

“Stars just don’t do that,” says Tabetha Boyajian, the astronomer who led the ensuing scientific investigation into the findings.

KIC 8462852 – better known as Tabby’s Star, after Boyajian – continues to befuddle citizen scientists and astronomers alike. While researchers have thrown numerous theories at the wall, some of which have partially stuck, they’re still searching for one hypothesis that explains everything.

How was Tabby’s Star Discovered?

“Stars do all sorts of things. They rotate with spots, they pulsate, they come in pairs of binaries, they have flares,” says Boyajian, who teaches at Louisiana State University.

But any other stars, exhibiting similar behaviors, all had explanations astronomers could see and detect – not Tabby’s Star.

While it appears that something is obstructing it, the star lacks signs of infrared excess, which typically occurs when dust is surrounding the star – acting like a thinner, fainter second star to reabsorb and emit extra light. Neither is it located by any regions that might’ve freshly produced a star with extra material around it.

“It’s just an ordinary star hanging out with something blocking its light. It’s very strange,” says Jason Wright, professor of astronomy and astrophysics at Pennsylvania State University.

“None of us could figure it out,” Boyajian recounts. “So, we decided to write a paper saying we don’t know what it is.”

That paper was published in 2016, in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. In it, the authors painstakingly combed through a multitude of hypotheses and ways to rule them out – ranging from something intrinsically within the star to swarms of fragmented comets to dust from a catastrophic, moon-forming collision.

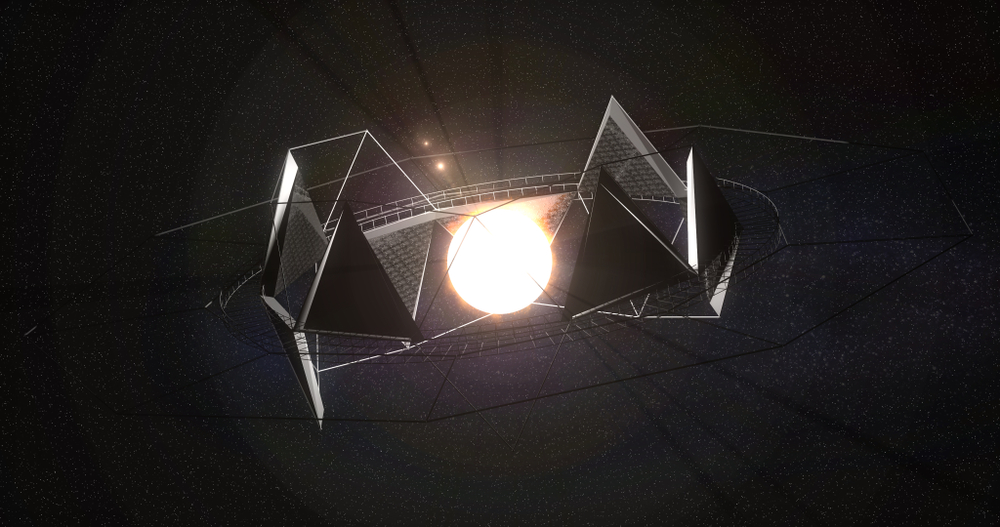

What catapulted the star into the media spotlight, however, was an idea Wright floated: It could be a swarm of artificial (read: extraterrestrial) structures.

Read More: Why Is Space So Dark Even Though The Universe Is Filled With Stars?

When Wright first learned of the star after Boyajian gave a talk at his university, he’d been working on his own paper imagining what Dyson Spheres might look like. What he saw in the data seemed to echo what he’d been reading and writing about.

“NASA accidentally did a SETI experiment, basically,” he says. (Dyson Spheres, he explains, refer to a collection of artificial material orbiting a star, like the interplanetary probes and satellites around our own sun.)

When SETI scientists investigated the star, they couldn’t find any evidence corroborating the theory. Of course, aliens were only one unlikely idea. Finding a natural explanation that fits everything remains elusive.

“The fact that Boyajian’s Star is rare […] suggests that the correct solution is an inherently unlikely one,” wrote Wright and co-author Steinn Sigurdsson in a 2016 paper.

Read More: Aliens Aren’t Responsible For The ‘Alien Megastructure’ Star

The Dimming of Tabby’s Star

A possible solution came along in 2017, when scientists witnessed Tabby’s Star dip in real time.

Thanks to a crowd-funding campaign Boyajian launched, astronomers had been observing the star with multiple ground telescopes since the Kepler mission. This time around, when it dipped again, astronomers observed it through several different colors of light, to better infer what kind of material might be blocking the starlight.

It wasn’t anything opaque – neither a planet nor a Dyson Sphere – because the colors of light dipped unevenly. Something was blocking blue light more effectively than it did red: a signature of dust.

But it didn’t work all the way. Dust could conceivably be filtering starlight, but it still didn’t produce any infrared excess. There was also the problem of the long-term fading.

Indeed, Tabby’s Star is not just strange for its intermittent dimming, but also because it’s been apparently fading over centuries. One study, which sparked many rigorous debates, looked at photographic plates of Tabby’s Star dating from 1890 to 1990. Between those years, the star had reportedly faded by around 20 percent.

Since then, other researchers have found evidence corroborating this find, mainly the fact that during the four years of Kepler observations alone, the star had faded by 3 percent.

“You can imagine, in 100 years, it could also drop by 20 percent,” Boyajian says.

Read More: Evaporating Exomoon Could Explain Weird Light Patterns of Tabby’s Star

Giant Dust Rings?

The latter paper put more weight into the initial study – though it was a bit annoying for astronomers, who now had yet another problem to account for, Boyajian says with a chuckle.

“If you have two weird things going on with the star – you have these short-term dips that we saw in Kepler, and then you have this very long-term trend of this dimming – Occam’s Razor says you have to have the same explanation,” she says. “The simplest is the best. You have to have the same explanation for both of them.”

As for where the dust around the star might’ve come from, or how it explains the long-term fading, Wright says bluntly, “No, I don’t know what’s going on.”

He personally entertains the idea that perhaps it’s a black hole with giant dust rings around it, traversing back and forth – which would explain why scientists aren’t detecting any infrared excess. But, he says, “No one has really worked out what such a disc would look like.”

In short, Boyajian says, “Nature is a lot more creative than we are.”

Read More: Black Holes May Have Sped Up Star Formation After the Big Bang

Future Research for Tabby’s Star

Now, scientists are turning to the James Webb Space Telescope in hopes for more clarity. Using the giant infrared telescope, astronomers have gathered more data to further constrain the possible configurations of dust around the star. Meanwhile, NASA’s TESS satellite detected two dips in 2019 unlike anything from even Kepler – they resembled a planet passing by.

“Trying to fold that into the explanation of what’s going around the star is particularly difficult, because it doesn’t match anything else that we see,” Boyajian says. Once again, astronomers are relying on citizen scientists to keep monitoring the star for any other dips.

“We don’t think this has anything to do with aliens, but nature does a lot of surprising stuff,” Wright says. “When you look at hundreds of thousands of stars, some of them are going to be weird.”

It would be immensely helpful if, among those weirdos, astronomers could find a second Tabby’s Star, to have even one extra reference point. But, in the meantime, the frustrating, mind-wracking challenge is part of the fun.

“I don’t think you’d do it if you [already] knew the answer in the end,” Boyajian says.

Read More: 7 of the Brightest Stars You Can See with the Naked Eye on Earth

Article Sources

Our writers at Discovermagazine.com use peer-reviewed studies and high-quality sources for our articles, and our editors review for scientific accuracy and editorial standards. Review the sources used below for this article: