How Sea Creatures Have Adapted To Life In Sunken World War II Vessels

Posted on Categories Discover Magazine

In March of 1942, the U.S. was only a few months into the Second World War. Already, German submarines lurked near the Atlantic coast, hunting for supply freighters and battleships. Late in the month, a U-71 detected the Dixie Arrow, an oil tanker carrying more than 86,000 barrels of crude oil from Texas to New Jersey.

The submarine fired two torpedoes at the target. Within a minute, the tanker was ablaze and sinking. Twenty-two crew members made it to safety; 11 died in the attack.

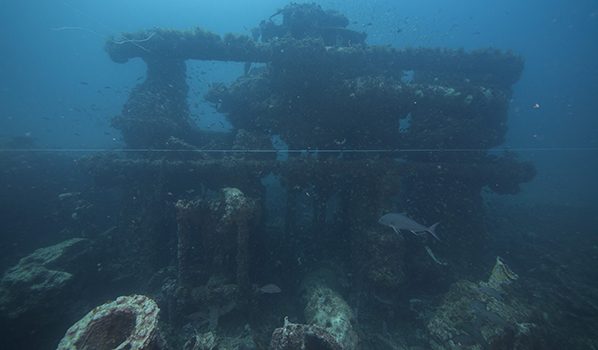

The tanker sank 90 feet to the ocean floor and landed upright. As the decades passed, the ship became part of the seascape. It is now one of many sunken WWII vessels where marine life has adapted as places to hunt, hide, or call home.

How Shipwrecks Impact the Environment

More than three million known shipwrecks have found their way to the bottom of the world’s waterways. Although ships have been sinking for thousands of years, scientific inquiry into these wrecks is more recent. In the 1920s, British scientist Lilian Lyle investigated a wreck in Scapa Flow (a body of water between the Orkney Islands in Scotland) and launched the academic study of sunken ships.

Studying shipwrecks has advanced in the last century to include a variety of disciplines, including archaeology, ecology, engineering, and oceanography.

Read More: What Are Eerie Ghost Ships and How Are They Impacting The Environment?

In some instances, scientists have found shipwrecks to be an “ecological treasure,” says Avery Paxton, research marine biologist at NOAA National Centers for Coastal Ocean Science.

“Shipwrecks can form hotspots for biodiversity. These places can be so alive with life, everything from tiny organisms smaller than my fingernail to the largest animals in the ocean,” Paxton says.

Shipwrecks can attract microorganisms and small creatures like sponges and corals. Fish of all sizes use shipwrecks as feeding grounds or places to hide. During migrations, sharks might use a sunken ship to rest during their journey, making some sunken ships the oceanic version of a highway rest stop.

Habitats and Shipwrecks

When a sunken ship reaches the seafloor, Paxton says it’s not forming its own habitat. “It’s sinking on to a habitat. Over time, it becomes part of the habitat,” she says.

How long it takes the ship to become part of the habitat depends on a lot of factors including the location, depth of the water, and ship material. Some ships, like the Dixie Arrow, are intact and land upright in the sand as if they are docked in the harbor.

The Dixie Arrow is now covered with living plants, corals, and sponges. Schools of fish of all sizes circle around the ship while sharks patrol nearby.

Other ships, like a freighter that was carrying sugar, are broken into pieces. The Manuela sank off the coast of North Carolina in June 1942 after a U-404 torpedoed it. The ship didn’t initially sink, which allowed all but two crewmembers to reach safety. A tugboat tried to tow it, but the Manuela went under.

Manuela, January 22, 1942, location unknown. (Credit: Courtesy of Steamship Historical Society)

The pieces are large and created a debris field, which became blanketed with plant life over time. The pieces now offer opportunities for fish to hide, hunt, or rest.

“It’s almost like these wrecks begin a second life. They have their first life in service, especially for WWII vessels, then when they wreck, they begin a second life,” Paxton says.

Propeller and stern section of Manuela. (Credit: Hoyt, NOAA)

Read More: Shipwrecks Teem With Underwater Life, From Microbes To Sharks

The Environmental Threats of Shipwrecks

Although scientists have identified WWII wrecks that have adapted well to the seafloor, most abandoned or sunken ships are problematic for the environment.

Scientists like Paxton caution that boaters shouldn’t think they are doing the environment a favor by intentionally sinking their unwanted vessels.

“Despite their ecological benefits, shipwrecks can pose risk to underwater life,” Paxton says.

Leaking Pollutants

When a ship sinks, it doesn’t land lightly on the seafloor. It can crush and destroy existing habitats, such as coral reefs. Paxton says sunken vessels can also leak damaging pollutants into the marine environment.

The Dixie Arrow, for example, was carrying more than 86,000 barrels of petroleum. For perspective, NOAA keeps a record of the largest oil spills in U.S. waters since 1969. The Dixie Arrow would be 15th on the list.

NOAA is uncertain what happened to the oil on the Dixie Arrow as the barrels are not with the wreck. In its description of the wreck, the authority describes the 86,000 barrels as lost at sea: “The cargo of fuel has long since been lost, and there is no remaining oil at the site.”

Invasive Species

Even if a sunken ship doesn’t destroy the habitat below or introduce pollutants, it might introduce an invasive species. Paxton says invasive species might also find a home in a sunken vessel and thrive in an environment where they might not have survived otherwise.

Off the coast of the Atlantic, for example, researchers have observed an invasive coral growing on sunken WWII vessels. The coral has the potential to alter the habitat by displacing native coral and sponges. As the habitat changes, smaller fish may no longer find it suitable for hiding, which means larger fish may no longer find it suitable for hunting.

Scientists and government agencies are trying to stop the spread of invasive species by removing sunken ships. They are also working on early detection techniques, and in some places like Florida, they are asking for the public’s help. Scuba divers and snorkelers are asked to report any sightings of invasive coral.

Authorities might be able to remove invasive coral if caught early. But once an invasive species starts to spread, authorities warn it is very difficult to eradicate.

Read More: This WWII Shipwreck Is Pouring Pollutants Into The North Sea

Article Sources

Our writers at Discovermagazine.com use peer-reviewed studies and high-quality sources for our articles, and our editors review for scientific accuracy and editorial standards. Review the sources used below for this article:

Emilie Lucchesi has written for some of the country’s largest newspapers, including The New York Times, Chicago Tribune and Los Angeles Times. She holds a bachelor’s degree in journalism from the University of Missouri and an MA from DePaul University. She also holds a Ph.D. in communication from the University of Illinois-Chicago with an emphasis on media framing, message construction and stigma communication. Emilie has authored three nonfiction books. Her third, “A Light in the Dark: Surviving More Than Ted Bundy,” releases October 3, 2023 from Chicago Review Press and is co-authored with survivor Kathy Kleiner Rubin.