Rare and Endangered, These Non-Parasitic Lampreys Are Far From Home

Posted on Categories Discover Magazine

In the summer of 2022, Luke Carpenter-Bundhoo, a researcher with the Australian Rivers Institute at Griffith University, wasn’t primarily searching for interesting fish species. Instead, he was investigating the effects of 2019-2020 bushfires in K’gari (formerly Fraser Island), the world’s largest sand island, which is located of Australia’s east coast, about 150 miles north of Brisbane.

Although Carpenter-Bundhoo wasn’t fishing for lampreys, he managed quite a catch — an Australian brook lamprey (Mordacia praecox) living about 600 miles from its known habitat.

The endangered species is especially unusual because it is part of a paired species — meaning that it has a relative with some physical differences that is genetically similar. Its closest cousin, the short-headed lamprey (Mordacia mordax), attaches to its prey with a ring of sharp teeth, then sucks its blood. M. praecox, which is nearly indistinguishable from M. mordax, dines by straining water through a filter in its mouth.

Catching the Australian Brook Lamprey

While sampling for fish, Carpenter-Bundhoo hauled in a couple he didn’t recognize. Upon closer inspection, he realized they were lampreys — but was surprised, because the eel-like fish don’t normally live in tropical waters.

“As a modern-day ecologist, you loosely operate on the assumption that someone else has already discovered what and where everything is,” says Carpenter-Bundhoo. “It wasn’t until I consulted the literature and a few colleagues that I was convinced I had come across something about 1,000 km north of where it should have been.”

One colleague put him in touch with David Moffatt, an expert on the species who had been quietly investigating unconfirmed lamprey records nearby on the mainland. Moffatt had found lampreys at several new sites, well into the tropical zone above the Tropic of Capricorn. They then shared notes, combined resources and wrote the study, which definitively identifies the species, maps where it lives, and discusses how to protect it.

Similar Looking Species

Protecting M. praecox may prove challenging, because the Australian brook lamprey looks the same as the non-threatened short-headed lamprey. Run-of-the-mill genetic tests cannot differentiate between the two.

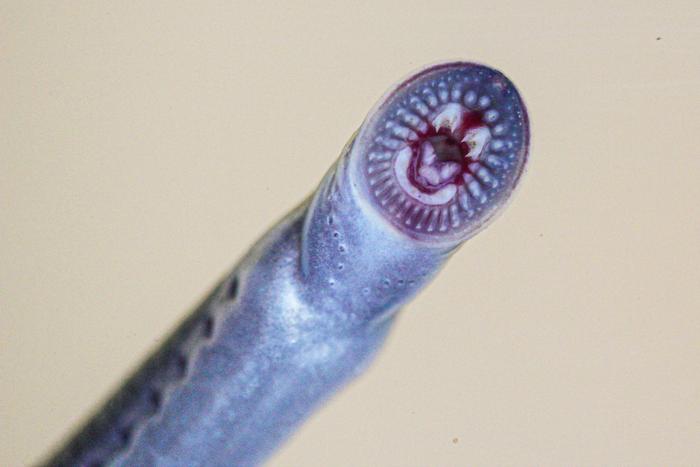

The best way to tell them apart is to catch a mature adult in the several months before they die, then examine their mouths. “Regular” adult lampreys have a ring of teeth connected by plates, but those plates dissolve in adult Australian brook lamprey.

“Basically, there’s only a several month window in their entire lifespan were you can distinguish them, and it’s rather tricky,” says Carpenter-Bundhoo.

Read More: 5 New Animal Species Discovered in 2023

Two of a Kind?

The ease at which Carpenter-Bundhoo found the unusual species was ironic, because Moffatt had been searching for them a few decades.

“The lampreys are an animal I have a love-hate relationship with,” says Moffatt, a researcher with Australia’s Department of Environment, Science, and Innovation. “I love them because I find them fascinating, but they have been very frustrating to work with — my side of the story has involved 20 years of perseverance.”

That perseverance hasn’t just involved finding the specimens, but also analyzing them genetically. The “paired species” concept complicates that work. The genetic similarities between the parasitic and non-parasitic versions could be a result of interbreeding — which gives rise to a series of questions, according to Moffatt.

“If they can inter-breed like that, are they really different species or just two different forms of the same species? Where will we draw the line? How do you want to define a species?” Moffatt says.

Read More: Here Are Just 4 Animals We Could Lose Before 2050

Article Sources

Our writers at Discovermagazine.com use peer-reviewed studies and high-quality sources for our articles, and our editors review for scientific accuracy and editorial standards. Review the sources used below for this article:

Before joining Discover Magazine, Paul Smaglik spent over 20 years as a science journalist, specializing in U.S. life science policy and global scientific career issues. He began his career in newspapers, but switched to scientific magazines. His work has appeared in publications including Science News, Science, Nature, and Scientific American.