The Ancient Primates of West Texas Resembled Lemurs

Posted on Categories Discover Magazine

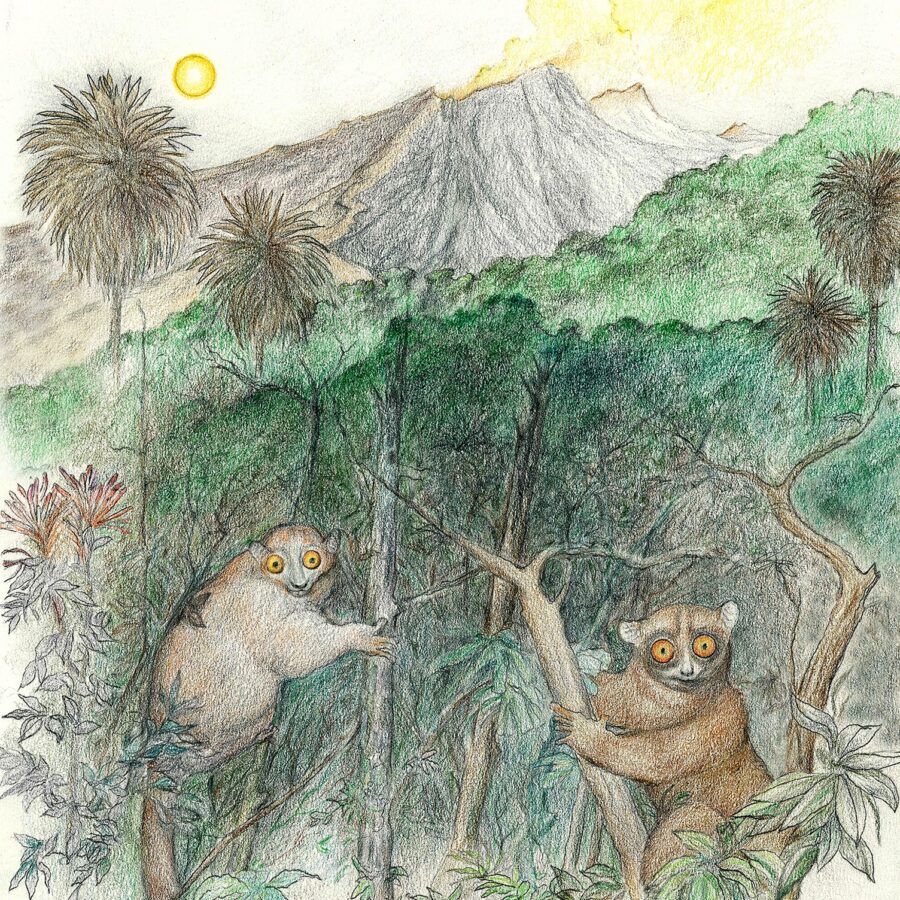

During the Eocene Epoch, between 56 and 34 million years ago, West Texas wasn’t the desert it is today. Rather, the ecosystem would have been made up of closed canopied tropical rainforests similar to what we might find in places like Costa Rica today. It was rainy and damp with humidity you could cut with a knife.

Many of the fossils found in this part of the world are preserved in the serpentine rivers that meandered through the forests in a landscape dotted with volcanic highlands. It was a world where rodents a plenty — large and small — scurried about the forest floor along with perissodactyls like tapirs, horses, and ancient rhinos.

In much the same way as you find various species of primates living in tropical rainforests today, the Eocene in West Texas was the perfect habitat for a burgeoning species of small and large primates unique to the area.

Omymyids During the Eocene Epoch

Christopher Kirk, an anthropologist at the University of Texas at Austin, is the author of a recent study published in the Journal of Human Evolution that highlights a species of small-bodied primates called omomyids. The species resembled lemurs found in Madagascar today. But these beady-eyed early primates weren’t actually related.

In the early Eocene Epoch, omomyids tended to be small with diets of insects and fruits, and they also tended to be nocturnal, says Kirk.

(Credit: Sarah Wilson) Chris Kirk with fossil

Coexistence with Adapidae

They lived at the same time as another group of North American Eocene primates called adapidae, which tended to be larger with diets of fruits and leaves.

This group was diurnal. As we move through the Eocene, says Kirk, things start to change. Adapidae disappear, and omomyids persist and start to get bigger.

“The omomyids that survive into this time period are no longer constrained to small body size,” says Kirk.

At a kilogram (about 2 pounds), Mytonius, a new species documented in Kirk’s study, is nearly four times the size of the other omomyid specimens found before it. The unusually large size was surprising and indicated that after adapidae disappeared, omomyids could replace them in their place along the food chain.

(Credit: Chris Kirk)

A picture of the holotype mandible of the 44 million-year-old primate Mytonius williamsae shortly after it was discovered.

Read More: 5 Skulls That Shook Up the Story of Human Evolution

Climate Change During the Eocene Epoch

Kirk’s research also shows that during the late Eocene, forests became more fragmented because of climate change, and primates started to evolve in isolation because there were fewer forests surrounding places like the Tornillo Basin of West Texas. “That’s why there are so many endemic primate species at that time,” says Kirk.

(Credit: Chris Kirk) Study area in West Texas

The Unique Evolution of Omomyids

These species evolve in isolation, which creates a world of creatures never seen before in the fossil record. “I didn’t expect to be spending so much time describing new taxa, but that’s the way it turned out,” says Kirk.

According to Paul Morse, a paleontologist at the University of Colorado, this research is sampling a time period in West Texas when we know from a global standpoint that things are getting cooler and drier, and we’re starting to see a less dense, more fragmented forest.

Read More: Earliest Gibbon Fossils Fill in the Gaps of Primate Evolution

How Climate Change Impacted Primates in North America

“Even while the global climate was shifting, there was this microclimate in West Texas that would have supported animals that we tend to associate with tropical and subtropical climates,” says Morse.

(Credit: Sarah Wilson)

Research team in the field

What Can Omomyid Fossils Teach Us?

Morse says that Kirk’s research is so important because omomyids have been poorly studied up until this point because it’s been difficult to find enough fossils to gain a good understanding of them. “The huge new sample size [of fossils] in this study helps bring some clarity and adds to our knowledge that the omomyids are expanding during this time period.”

Are Omomyids Related to Modern Humans?

We’re just beginning to scratch the surface regarding our understanding of primates during the Eocene in North America. These are the primates that would later grow in size and sophistication, spreading all over the globe. In fact, the consensus is that omomyids are distantly related to the primates that would one day make their way to the very top of the food chain and become modern humans.

(Credit: Sarah Wilson)

Research team in the field

Read More: Long Before the Arrival of Humans, a Strange Little Primate Populated the Western United States