This Bronze Age Power Took Notes on Ancient Rituals, and We’re Still Deciphering What They Say

Posted on Categories Discover Magazine

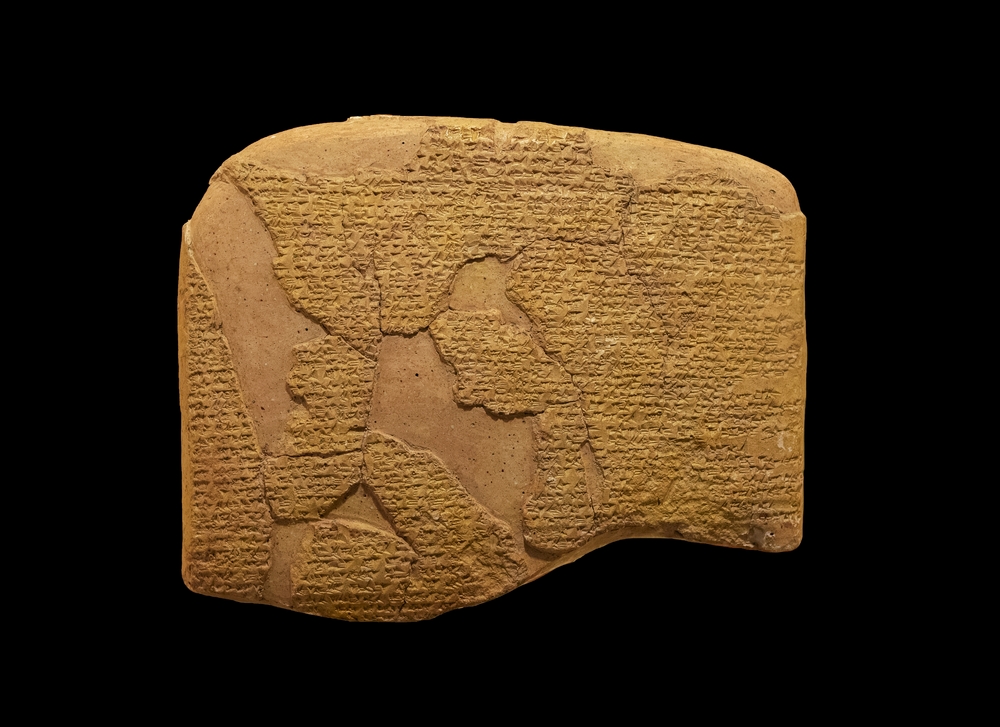

The Hittites wrote, and they wrote a lot. In their home turf of Anatolia around 4,000 to 3,000 years ago, Hittite writers recorded state dealings and decrees, myths, rites, and religious rituals. They wrote down the details of their diplomacy, their combat, and their commerce, and they described Hittite celebrations, all on the surface of scratched clay tablets, written in a script called cuneiform.

Of course, the thousands of tablets that still survive today are some of the most important records of Hittite culture and civilization. Yet, they are also records of the cultures and civilizations that surrounded the Hittites, including their neighbors, allies, and adversaries.

This year, researchers announced that they’d discovered a reference to a new Indo-European language on a tablet from Hattusa, a UNESCO World Heritage Site and the former capital of the Hittite civilization. The tablet is over 3,000 years old and testifies to the Hittites’ interest in foreign traditions and languages.

So, who were the Hittites, exactly, and what does the tablet say about their history?

Who Were the Hittites?

Between 1700 B.C.E. and 1200 B.C.E., the Hittites ruled over much of Anatolia, the peninsula that contains most of the terrain of modern Turkey.

What Were the Hittites Known For?

Famed for their metallurgy and their mastery of chariots, they created one of the first major civilizations of West Asia, centered on the city of Hattusa.

At their peak, their powerful empire extended south to modern Syria. There, the Hittites encountered the Egyptians, one of the other prevailing powers of the time. Fighting for control of trade routes and resources, the two foes famously clashed in the 13th century B.C.E. at the Battle of Kadesh, which concluded with the signing of what’s widely considered the world’s first international peace treaty.

Read More: Ancient Empires Used Bioweapons to Strike Terror More Than 3,000 Years Ago

What Happened to the Hittites?

Almost a century after the agreement, the Hittites’ expansive empire splintered into smaller city-states. Archaeological evidence indicates that Hattusa was burned and abandoned around 1200 B.C.E.

The Hittite Empire and the Bronze Age Collapse

The capital’s fall coincided with the so-called Bronze Age Collapse, the simultaneous decline of several Mediterranean civilizations during the 13th and 12th centuries B.C.E.

Though the catalyst of the Bronze Age Collapse is still subject to debate, it is often tied to the arrival of the so-called “Sea Peoples,” whose invasions brought destruction to much of the Mediterranean, and several other factors, such as the onset of a severe drought.

Read More: Tree Rings Hint at the Fall of the Hittite Empire

The Cuneiform Tablets of Hattusa

Today, all that’s still standing in Hattusa are some of city’s temples, royal residences, and fortifications, including the ruins of the Great Temple, dedicated to the god Teshub and the goddess Arinna. Strewn with smaller artifacts, these remnants act as a window into the world of the Hittites.

In fact, researchers have found around 30,000 cuneiform clay tablets at Hattusa throughout the past century, including the “Proclamation of Annitas” that describes the founding of the Hittite civilization and the “Treaty of Kadesh.” Together, these texts reveal valuable information about the Hittites’ history, politics, religion, and relations with other regional powers.

Read More: Decoding Cuneiform, One of the Earliest Forms of Writing

What Languages Were Hattusa Tablets Written In?

Though the majority of the tablets from the archives at Hattusa are written in Hittite, the oldest written Indo-European language known today, some include passages in other Indo-European languages (like Luwian and Palaic) and non-Indo-European languages (like Hattic).

The latest addition to this list was added in September, and is believed to be the language of the land of Kalašma, in the Hittite hinterlands, to the northwest of Hattusa in the area now occupied by Bolu and Gerede. Researchers found the new Indo-European language on a religious ritual tablet. Such texts were written by scribes under the behest of Hittite royals, researchers report, and included records of foreign rites in related foreign tongues.

Read More: How Do Archaeologists Crack the Code of Ancient Languages?

What Were the Cuneiform Tablets Used For?

The Hittites were “uniquely interested in recording rituals in foreign languages,” Daniel Schwemer, the chair of Ancient Near Eastern Studies at Julius-Maximilians-Universität Würzburg and part of the team deciphering the new language, said in a statement. In fact, though the Kalašman portion of the text is still “largely incomprehensible,” its presence alongside a cultic text suggests that it refers to foreign religious rituals.

Analysis by Elisabeth Rieken, a specialist in ancient Anatolian languages at Philipps-Universität Marburg, suggests that the new language belongs to the Anatolian-Indo-European grouping and shows similarities with the already known Luwian dialect, “despite its geographic proximity to the area where Palaic was spoken.”

The researchers plan to investigate the similarity of their find to other Anatolian-Indo-European languages in the future, revealing more about the ancient Hittites and the people in their peripheries.

Read More: Eight Ancient Languages Still Spoken Today