Ecologists strive to revive struggling moth species

Posted on Categories Discover Magazine

This story was originally published in our Nov/Dec 2023 issue as “Moth to a Flame.” Click here to subscribe to read more stories like this one.

Robert Hoare first spotted the elusive Izatha psychra, an endangered moth in New Zealand, on a warm night in 2005. At the center of the country’s South Island, amid the fenced flats and sloping hills of the Pukaki Scientific Reserve, the entomologist erected a generator-powered light trap. Then, an hour before midnight — just as the generator’s fuel threatened to peter out and plunge everything into darkness — he glimpsed fluttering wings and a flash of gray.

Hoare is one of only a handful of people who can claim to have encountered the moth, as fewer than a dozen have ever been seen. All of these sightings occurred either in the dry shrublands and scrub of the Mackenzie District that encompasses the 79-acre reserve, or in the neighboring district of Central Otago roughly 140 miles south.

However, the quest for I. psychra now covers a much smaller expanse. In August 2020, a fire that began near the turquoise waters of Lake Pukaki to the east raged across more than 7,600 acres of forest and scrub — including most of the Pukaki Scientific Reserve, damaging its threatened and declining vegetation. “The reserve was made naked by the fire,” says Eric Edwards, a science advisor at New Zealand’s Department of Conservation. “Before the fire, you wouldn’t notice much of the rock because the shrubs were fully leafed. Then the fire came through and burned the small twigs and leaves away.”

I. psychra’s sparse population depends on the reserve’s old-growth shrubland for food and shelter. And despite their limited numbers, the moths play a vital role within the ecosystem. The genus is known to feed on deadwood, dead leaves, leaf litter or lichens, according to Hoare. Though there is no real nutrition in this detritus, the moths digest largely fungal content and release nutrients from that back into the ecosystem.

When the blaze destroyed most of this habitat, it immediately shrunk the chances of survival for the already struggling species.

Unburnt lichens like these alerted Eric Edwards and colleagues to the possibility that some moths had survived the blaze. (Credit: Eric Edwards)

Strength in numbers

I. psychra’s discovery dates to the late-19th century, when the naturalist John Davies Enys collected the first known specimen, now residing in London’s Natural History Museum. He encountered it near Porters Pass, in the mountains some 186 miles northeast of the Pukaki Scientific Reserve. Since then, sightings have been extremely rare, and researchers have yet to produce even a rough estimate of the moth’s overall numbers. Hoare, currently a senior researcher at New Zealand’s Manaaki Whenua Landcare Research, has seen three, all males. “Because the female moth has never been seen, we guess that it doesn’t fly very much,” he says.

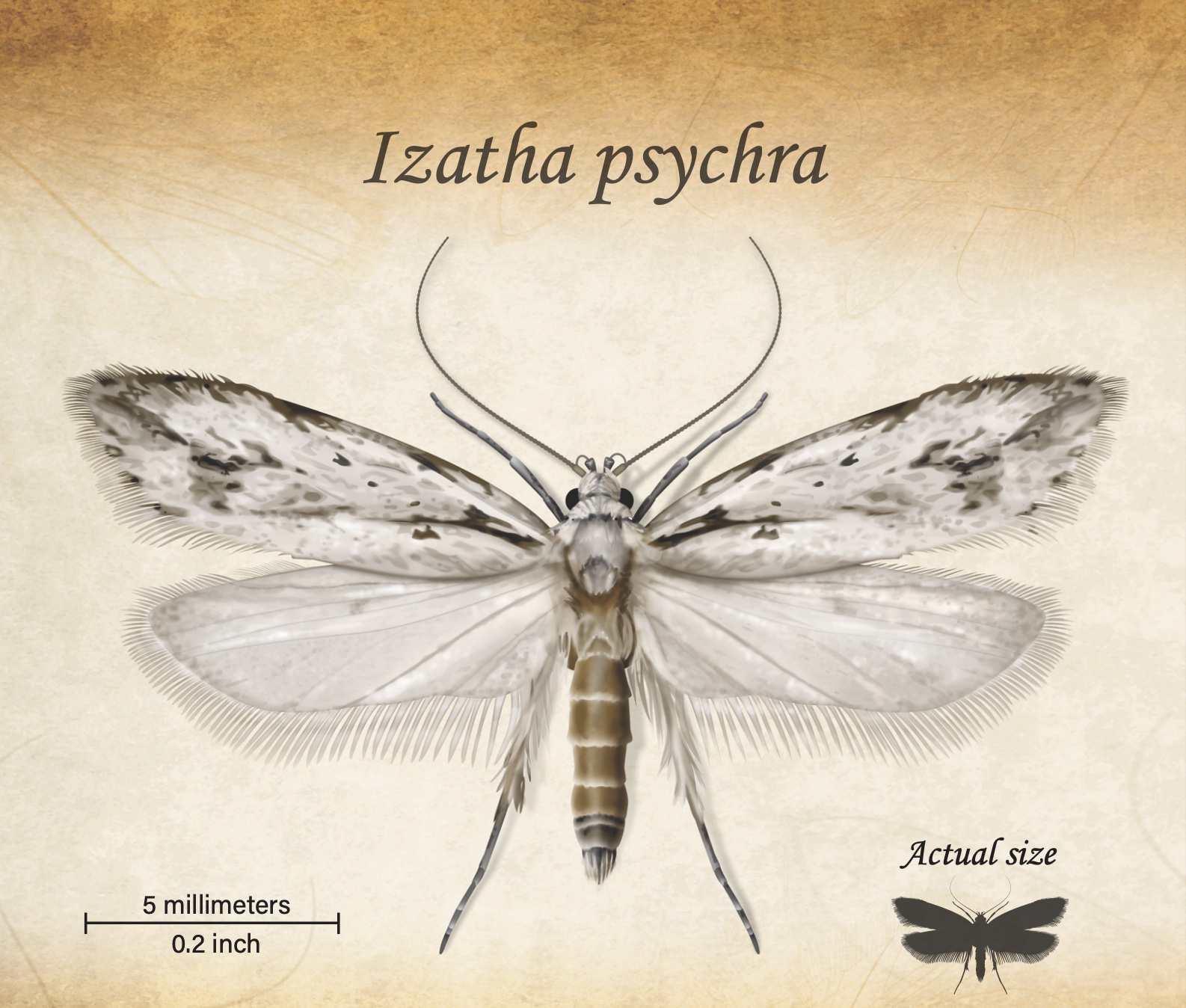

Adding to this sense of mystery is the moth’s tiny size and nondescript appearance. Only around a third of an inch long and three-quarters of an inch wide with outstretched wings, I. psychra’s pale-gray color allows it to blend in with the surrounding scrub. Hoare, however, believes its enigmatic nature has more to do with the reduction in its habitat. Those strongholds are facing the threat of destruction from weed invasion and a warmer, drier climate that increases the risk of wildfires — such as the 2020 Lake Pukaki fire.

Five months after that event, a team of ecologists including Edwards surveyed the reserve to search for the I. psychra moths. They turned up a tiny, 1-acre pocket of dense shrubland that proved impenetrable to the blaze; underneath these thick shrubs was a small gully with undamaged deadwood, leaf litter and lichens in it. The oasis was a likely site for moth survivors.

On a dry, windless day, the team returned to the remnant of unburnt land and set up a trap using light. “It’s like going for a picnic,” Edwards explains. The team spread a white sheet on the ground, placed a light source in the center, then waited for the guests to arrive. “The moths will settle around the light, and you can look at them and think about what species they might be,” he says.

Under the cover of darkness, half a dozen or so were drawn to the light at a time, an amalgamation of species that landed and settled before taking to the skies again. Then, Edwards saw something resembling I. psychra — a glimmer of hope for the species. The Izatha genus are known as lichen tuft moths. That’s because most of them have little scale tufts on their wings, which are slightly curved or curled. “It helps them look a bit more like rough bark or lichen,” Hoare says. “[But] Izatha psychra hardly has these. They’re small and inconspicuous scale tufts.”

Edwards, still uncertain of what he had witnessed, took photos of two male moths and sent them to Hoare, who then examined their features. From their pale-gray color and scale tufts to their wing markings — the little black streak at the base and the eye-shaped mark in the middle — Hoare was elated to find that the moths perfectly matched the I. psychra species. “Anytime you have something that’s rediscovered or saved, that’s a good story,” he says.

(Credit: Samantha Gale)

Pieces of the puzzle

The future of the species is ultimately tied to the region’s recovery — still in its early stages. “There’s a lot of still just blackened, burned sticks and stumps, but some plants are starting to regenerate,” says Dean Nelson, a senior ranger of biodiversity at the Department of Conservation who oversees the reserve. Indeed, signs of new life abound: Sprouts spring up from the bottom of shrubs and tufts of tussock grass bounce back in open areas.

Protecting the land from invasive weeds and mammalian pests is another important piece of the puzzle. Immediately after the fire, Nelson and his team rebuilt the damaged fence, with a double barbed wire on top. The hope is that this will be enough to keep rabbits, pigs and wallabies out, all of which chew on the reserve’s plant life and slow vegetation recovery.

Efforts are also underway to clear out the surrounding invasive pines, which cover nearly 4.5 million acres of New Zealand. “Wilding pines were part of the problem for the fire because they burn very hot and exacerbate [it],” Nelson says. “Fire in grassland can burn quickly, but it’s generally a lot less intense than fire that originates in pine forest.”

Nelson estimates it could take as many as 50 years for the reserve to recover. But hope continues to burn bright for I. psychra, with two more sightings of the species in late 2022 — this time at the dry, shrubby lands of Mount Buster, some 112 miles south of the Pukaki Scientific Reserve.

“As scarce and hard to find as it is, it has brought a fresh new look at the landscape by those who care,” Edwards says of the species. This shift in perspective is what Māori, the Indigenous people of New Zealand, call kaitiakitanga, or guardianship and protection of the environment. It stems from the Māori worldview acknowledging the intricate ties between humans and the natural realm.

“It is invoking a form of stewardship that communities of people in New Zealand are now tuning in to,” Edwards says. And when it comes to I. psychra, saving the moth’s habitat could help bring the species back from the brink.